WRITING AFTER SUNSETS

For years, I maintained a separate blog called writing after sunsets as a place for my thoughts on writing, reflections on teaching, and an outlet for writing that matters to me in ways that make me want to control how it is published. It has also been, from time to time, a platform for the work of others I know who have something to say.

Now, with this site as my central base of online operations, I’m folding that blog into the rest of my efforts. All previous content is here for easier access, but the heart of writing after sunsets remains in both my earlier posts and those to come.

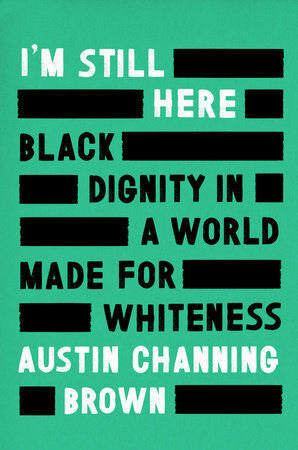

Books — I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Still Made for Whiteness

That makes this a book a service and gift to white readers Brown was not obligated to provide us.

As part of my sabbatical, I read widely and by choice, dipping into books I’ve wanted to get to but could not as well as several that came out recently. As part of my post-sabbatical reflections, I’ve written several short but specifically focused responses to some of what I read. These responses, like the one below, focus on one element each from a select list of readings and represent the best of what I encountered.

I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Still Made for Whiteness

Austin Channing Brown, Convergent Books (2018)

Find the book here. Visit Brown’s website here. And check out her show The Next Question here.

Before I read I’m Still Here, I caught an interview with author Austin Channing Brown on the Seminary Dropout podcast that opened with her recounting how her parents named her Austin as a way of preventing people from responding to her out of their prejudices before they’d actually met her.

This, of course, collapsed for her when a librarian looked at her name on a library card and said it couldn’t be hers. And there it was: regardless of how Black people attempt to engage or adopt dominant, normalized notions of white culture, they end up excluded because that is the nature of white supremacy.

Sadly, as Brown’s book describes in various settings, this is exactly the way that Evangelical organizations end up treating Black people who have been invited in, ostensibly, to address the very issue of lacking diversity. This sad irony is distilled in the following passage:

In this way whiteness reveals its true desire for people of color. Whiteness wants us to be empty, malleable, so that it can shape Blackness into whatever is necessary for the white organization’s own success. It sees potential, possibility, a future where Black people could share some of the benefits of whiteness if only we try hard enough to mimic it….Rare is the ministry praying that they would be worthy of the giftedness of Black minds and hearts (79).

This insight, in my opinion, is critical both in Brown’s decision to stop playing the diversity game by rules that maintain the status quo and for reshaping the issue for those of us who may not understand how our choices are exactly what keep those rules in place in the first place.

The starkest racial divides often exist in spaces so deeply ingrained in the systems and thinking operating so seamlessly in white culture that they’ve been rendered invisible. They manifest only in the erasure of Black people.

By nature, this erasure of others also sweeps away the very traces of its existence in the eyes of those who benefit from it. This requires marginalized people to choose: do they continue to conform or do they resist in an attempt to be rendered visible despite all the potential costs that come with that resistance?

I’m Still Here, then, is the story of Brown’s path to claiming her own space by stepping outside environments that made her have to ask to be seen in the first place. It’s also her moment of pivoting away from trying to create messages for a predominantly white audience who aren’t listening in ways that enable hearing they’re being told.

That makes this a book a service and gift to white readers Brown was not obligated to provide us. To read it as anything else is a vestige of a power structure that demands every message must protect the sensibilities of a group that actually needs to see and feel the pain we cause others—as much as it is possible for us to do so—in order to understand our need to change.

Note: This book made the New York Times Bestseller List this week, and rightfully so.