WRITING AFTER SUNSETS

For years, I maintained a separate blog called writing after sunsets as a place for my thoughts on writing, reflections on teaching, and an outlet for writing that matters to me in ways that make me want to control how it is published. It has also been, from time to time, a platform for the work of others I know who have something to say.

Now, with this site as my central base of online operations, I’m folding that blog into the rest of my efforts. All previous content is here for easier access, but the heart of writing after sunsets remains in both my earlier posts and those to come.

Harry Chapin

I hear people say all the time, “We didn’t really expect (insert child’s or children’s name[s]), but now I can’t imagine life without him/her/them.” I’ve said it myself, about all three of my beautiful children. But I’m lying when I say it and selling my imagination short. Of course I can imagine life without them, and in many ways what I see looks good. Looks easier. Looks less complicated. Looks better in some very tangible ways.

And this is how I know I really and actually love them. Even in the moments when I shouldn’t, when it would not be selfish not to, my love for them persists. In a sense, it really isn’t “my” love at all, I guess, but something greater that comes from outside of me and I am grateful for it; I am grateful for them and the ways I would not be me if I were “just” me.

***

I think we almost always know when we are taking something for granted, despite our protests to the contrary. It’s actually thinking about what we’ve lost by doing so that sneaks up on us—the feeling of responsibility we allow busyness to push away until we can no longer ignore it. But I’m certain it’s better to feel that guilt and shame than it is to lose what it is we took for granted in the first place. Unfortunately, there have been too many times when I’ve hoped that my children will agree with me when they’re older. And my family members. And my wife.

Songs that Sing Us

Throwback to the time I met my favorite songwriter, Jon Foreman, and the guys from Switchfoot. Who's writing your life in lyrics?

Every single person should actively seek out that songwriter whose lyrics speak his or her life. Not songs we admire or appreciate or even love. These people write songs that feel like our own thoughts, but better or clearer or more useful than we could make them ourselves. We don’t listen to these songs. We remember them before we’ve ever heard them.

I’ve found mine. Grew up in the same town as him. That’s likely one of the reasons I love his work so much. But more, in his lyrics I hear the same wrestling match I find myself in. Doubt and faith. Anger and grace. Fear and resistance. More questions than answers. In it all, however, there is a hope that refuses to be anything more than present, even when it feels like it shouldn’t be. Sometimes, it’s as if I’m hearing his side of a conversation the two of us are having. I’m pretty sure that’s the greatest compliment I can pay his work.

I hear people say all the time that a particular artist inspires them. Moves them. Challenges them. I say, look for a writer whose words feel ultimately familiar and foreign in the same moment. And let them take you to church.

***

Nostalgia alert: I miss songs with space in them—solos and silence and moments when we weren’t necessarily waiting for the next line.

Anti-nostalgia alert: That doesn’t mean that every song with space built in earns it. I’m looking at you prefabricated 80s metal bands with paint by the number guitar solos and ridiculous electronica/house/sample-recyclers who think the mere act of looping is art.

Double nostalgia alert: I miss when making enough good songs to warrant an entire album was mainstream.

Double anti-nostalgia alert: There are so many artists who should never make another album. Just keep making singles until your 15 seconds pass.

Binary (De)code

A distillation of some larger thoughts:

Faith. I do not think that word means what you think it means (thank you Mandy).

Certainty is the religion of the day, and it cuts across a broad swath of congregations. Some are utterly certain of their version of God. Some are utterly certain that versions of God mean there is none. Some are utterly certain of the material world at the expense of the spiritual. Some are utterly certain of the Spirit at the expense of the material experience right in front of them.

It’s as if doubt is the toxic influence in culture. I’m fairly certain that’s not our problem.

***

The so-called division between science and faith is not so much a debate as a mutually assured form of keeping oneself from fully engaging either. Both ends of the spectrum of voices that take up this form of rhetorical trench warfare do so at the expense of their own legitimacy in claiming answers of certainty in the face of the unanswerable. That is neither the scientific method nor legitimate faith. Then again, humans do have a way of claiming a sense of rock-solid certainty without earning it in any meaningful way. Maybe the better path comes from allowing both to wrestle with mystery rather than fabricate an exclusive, totalizing certainty. Maybe the better path is to always remain conscious of the maybe.

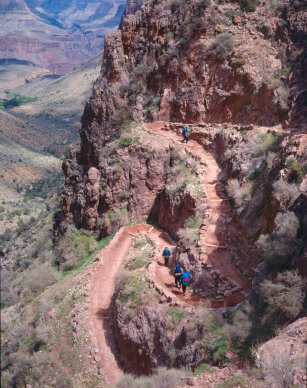

Single Track Thinking

Photo Credit: http://www.nps.gov/

I am deeply disenchanted with almost any form of singular narrative. The more people claim a singular sense of anything humans live through, the less I can take what they have to say seriously. Racial experience. Political primacy. Educational success. Socioeconomic “reality.” Lived experience. Religious norms. Gender expectations. When any voice or collection of voices claims to hold “the” representation of these and other complex, dynamic, multi-faceted experiences, I’m out. We fear complexity and construct simplicity, inventing lies that hurt others and us just to avoid the messier truths of reality.

***

On climate science:

Someday, I hope we realize the full extent of our interdependency with the planet. It may be our best metaphor for our connection to the divine, right down to the way we disregard it at every turn.

Listen Up

Photo Credit: http://www.thehearingclinicuk.co.uk

Listening is exhausting. Seriously, nothing highlights our radical self-centeredness as a species quite as much how far we will go to avoid listening to what others have to say. We’ve built monuments, communities, and systems that destroy all manner of life simply to keep from hearing each other.

***

My younger son, almost four years old at the time, sat in church with me one Sunday rather than go to his class in the preschool. Halfway through the sermon, he looked up and said, loudly, "This story is taking too long!" I hope more than just our pastor hears Judah, because he nailed it.

Story: Essential Foils

Stories are more important than details. Meaning must be made, even if you happen to think that everything is meaningless. Fiction is as true as truth when it wrestles with that great, gaping maw of life’s randomness. I'm not advocating the search for a grand narrative behind all of this. If all we experience is connected, we're not equipped to find the thread that holds it all together, even as sure as I feel that there is an intent in this all. Rather, I believe everyone should see the world in the context of story. Not one they are a part of, but one they are authoring. If you see life as a story unfolding as you move through it, your passivity actually hurts the people around you. If you see yourself as having been given authorship in your tiny piece of the larger narrative, your actions matter whether or not you think they do. In the cosmic scale, we write our universe because as broad as our reach has become, we are still always and ever beholden to this present tense second.

***

Every single human should take a creative writing class. I’m not saying that everyone should be a writer (see my earlier passage regarding whether or not I think I should be one). But everyone should consider stories from the perspective of a maker rather than merely a listener or reader. It will definitely change the way they see the people around them. It will teach them about those people, and, in contrast and conjunction, themselves. It might even teach those willing to listen a little something about God.

Running to Stand Still (is still my favorite U2 song)

There was a time when running wasn't a euphemism in my life...

Photo Credit: Elaine Funk

When I was a teenager, I ran track as a break from playing basketball year-round. I loved the way races shut down the outside world. I ran sprints—100, 200, 4x100, and the 400 if my coach felt like watching me pass out—and the mere seconds from gun to done were as close to meditation as I got.

I remember once, as a young kid, getting scared while running as fast as I could on the elementary school playground. I stopped and looked around to make sure I hadn’t started a tornado because, in my head, it felt like I had. I wasn’t that fast, but the speed we create when we’re little makes the world feel slower in ways we are not prepared to handle.

My final competitive 200 meter race started well and ended very poorly. I was on pace to run my best time ever in my best event and maybe—maybe—beat a guy I’d been losing to for four years. Coming out of the turn, my hamstring twinged, then seized, and then tore. I fell flat on my face. The race ended, some teammates helped me off the track, and we went on to lose the overall league championship by two points. If I’d finished second, we’d have won by six. It still bothers me.

When I was in sixth grade, my brother goaded me into challenging my 43-year-old father to a foot race. We ran about 40 meters and Dad destroyed me. I only found out after the race that he had been a sprinter in college. Hindsight and all. Fun fact: I never ran the 100-meter dash faster than my father.

I coached high school track for a while. One of my favorite drills was to send the entire team on a four-mile run at the very beginning of the season. I mapped out the route and sent them on their way. Then I drove to the run’s midpoint, located near a Baskin Robbins ice cream store, bought a cone, and sat under a tree while they panted by. As they passed, I told them I wasn’t tired yet. I like to call that team bonding. You’re welcome, Cardinals.

When I run now, there’s no danger of the kind of temporal displacement I felt as a kid. I haven’t sprinted in years. If I ran the 200 now, it would have to be timed on a sundial. I still feel my hamstring, but now it’s joined by an arthritic ankle, reconstructed knee, repaired hernia, and general sense of being elderly. I’m pretty sure a kid who saw me running recently went out of his way to push the crosswalk call button for me out of altruistic concern for my wellbeing.

***

When I was 19, I woke up one morning in my dorm room with blood on my pillowcase and the acute inability to make sounds happen with my voice. I went to a specialist who sent a scope up my nose and down into my throat, grunted, sighed, pulled the scope out, and set it on the tray next to him.

“Well, you won’t be singing anymore.”

“For how long,” I asked, accustomed to taking brief breaks that let my instrument recover.

“Ever. At least in any consistent way. Sorry. You just have a poorly constructed system.”

Twenty-one years on and it still feels like getting punched in the throat to even type those words. Singing was part of my identity. I miss it every day.

What have I learned from it? That losing sucks. That I could have done everything possible to save my voice and still lost it. That I never gave singing the credit it deserved in terms of how much I needed it. That I got to do some great things because of my voice and feel, in many ways, cheated by what happened.

Mostly, I learned that I was called to do something else and that discovering who and what we are supposed to be isn’t always a rapturous experience.

Successful Failure

We are the product of our failures much more than our successes. Success breeds self-assurance that ends in repetition. Failure breeds self-awareness that ends in re-creation. Only one of these is growth.

That sounds like a bumper sticker or, for the kids in the audience, a meme. So let's mess that up a bit. If you reflect only on what you've done well, you kinda suck. That nostalgia for your own history blinds you to the ways you need to be better. It keeps you from realizing that the measures of success aren't at all what you're holding onto.

Now, I'm not advocating a pathological fixation on all the ways we don’t get it right. For more on this, refer to my note on grace and realize that the same dirty, costly grace we need to show others can and should also be shown ourselves. It already has been. But this is reality: failures are who we are. Successes are the blessings we were fortunate enough to be standing next to when they happened.

***

I firmly believe that we are as much or more the result of what I call intrapersonal barriers as we are our willful constructions of who we want to be. Put another way, we perceive these barriers as the shadows we must grow out of to be seen as individuals by the world around us.

These shadows are so often the chimeras (no disrespect to Baudelaire) we carry through adolescence and into the rest of our lives; a powerful force in the shaping of who we are as a person, both in our own estimation and that of the people around us. To be sure, we make many defining choices. But it’s at least as important to note the choices we didn’t make that set up so many of those we had to.

Here are my three most prominent, in no particular order:

Growing up in a place where I was not a local and could never afford to appear to be.

Primary example: We were never poor, but we didn’t have all that much. In junior high, I transferred to a private school on scholarship. In the summer, my dad and I painted the bathrooms to hold onto that financial aid. Many of my classmates went on resort vacations or stayed in their “other houses.” In this case, it’s not about equating what I didn’t have with what people in poverty don’t. It’s about how comparing myself to everyone else established my “normal” for a long time.

Being the son of a pastor with no designs on being one myself.

Primary example: While trying out some adult phrasing in third grade, I told my friend Jason to shut his damned mouth. My first grade teacher overheard me and, with literal hands on equally literal cheeks, said, “Michael Clark! What would your pastor father say if he heard you say that?” Repeat that scenario for the next fifteen years.

Playing basketball in the same place as my brother (a MUCH better player).

Primary example: A referee stopped me during one of my first varsity games as a freshman. “Clark? Are you related to Paul Clark?” “Yeah, he’s my brother.” “Huh. I expected you’d be better.” For the record, my brother is eight years older than me and had to keep me from quitting the sport I love most just before my senior year.

In the Hollow of the Quiet

This may be a bit lot more vulnerable than my passage about whether or not I’m any good at writing. At least there’s some uncertainty there. My struggle with depression is, on the other hand, much more certain than I’d like it to be. It’s there, the same way that in the middle of the day when the sun is at its brightest, the nighttime darkness is merely a half revolution of the planet away. In the middle of any emotion—the happiest happiness, most joyous joy, most contented contentedness—it is just as possible that I will crash as when I am weary or sad or “most likely” to “get” depressed.

That depression is not about its circumstances has been the most difficult lesson to internalize. I feel so guilty about my bouts with it. I mean, what do I have “to be depressed about?” I have the best partner I can imagine in my wife. I have three legitimately fantastic children. I have a family who loves me and who I love. I have in-laws I feel the same way about. I have friends. I have a fantastic job. In short, I have all the things that should stave off depression.

Taken a step further, I have my faith. It is the ultimate hope I cling to, in the face of all of it. But within my community of the faithful, the prevailing logic is that should be enough. That when I am depressed, I suffer from a lack. I am not being thankful enough. Not grateful enough. Not humble enough. Not faithful enough.

I’ll be the first to admit that I have thought all of these things about myself. More honestly, in the middle of my darkest, heaviest, most disconsolate places, I’ve lodged these accusations against myself, drawing an easy conviction in the court of my heart.

Before I become too easy a caricature, yes, I am aware depression is a mass of chemical, neurological, biological, seasonal, circumstantial, and inter/intrapersonal complexities. It’s not always only a matter of praying the gray away.

That’s what makes it so difficult. If, as I posit later, doubt is the crux of faith, then I find myself at an uneasy crossroads because it would also seem to be the crux of depression. I wish I had an answer to why those two seem to intersect so seamlessly. Probably because grace requires empathy for the entirety of the human experience and we are so infrequently able to see that.

***

On silence:

I have a slight case of tinnitus, likely the product of flouting headphone volume warnings as a kid.

I live in the Los Angeles area. There are so many noises around me I don’t even register consciously that I’m fairly certain we all suffer a form of deafness doctors just haven’t given a consistent label yet.

My favorite place in the world is on the shore of the Pacific Ocean, in a place called Cardiff by the Sea, California. I like it best when the tide is out and the fog is in. I think of these conditions as a more real form of silence.

A few years ago, I hiked to the top of the tallest mountain in the lower 48 states. When I reached the summit, there were at least thirty other people up there. They would not shut up.

I like my wife a lot. She’s my best friend. When she’s not talking to me, I find myself filling the quiet gaps, trying to goad words out of her. I despise the thought that one day I won’t get to hear her anymore.

Silence is not golden. Understanding why sound matters because of it is.

Do I Not Amuse You?

I am funny and I feel guilty for it. I have no idea what to do with that disconnect within myself. That could be why most of what I write tends to be serious. Or, maybe I'm not as funny as I think. It's probably that.

***

People who know me personally and read my work often find the two discordant. They wonder why there is not as much humor in my stories on paper as there is in the ones I tell. One reader, after finishing a piece I wrote, told me I “traffic in tragedy.”

That’s funny. I prefer to say tragedy, so often, traffics in us.