WRITING AFTER SUNSETS

For years, I maintained a separate blog called writing after sunsets as a place for my thoughts on writing, reflections on teaching, and an outlet for writing that matters to me in ways that make me want to control how it is published. It has also been, from time to time, a platform for the work of others I know who have something to say.

Now, with this site as my central base of online operations, I’m folding that blog into the rest of my efforts. All previous content is here for easier access, but the heart of writing after sunsets remains in both my earlier posts and those to come.

20-15-10

And that’s what hit me about my workiversary. I didn’t see it coming because I’m perpetually too busy with that course of study. I’m not perfect. Hell, I’m not even exceptional.

Photo by Carli Jeen on Unsplash

I filed grades for my last class of the year this past Friday and it occurred to me that this is a season of professional round numbers for me.

The end of that summer course marks the completion of my 10th year as a full-time professor of writing, my 15th teaching in higher education, and my 20th as an educator.

Not bad for a job I initially avoided and then took on as a two-year stop-gap to “see what I actually wanted to do” after I left daily journalism.

Before you get the wrong impression, this is more a commentary on how my not seeing the significance of this year was the result of a very different realization. I’ll save the sloppy nostalgic tour of my career for 30-25-20.

I really didn’t consider the numeric synergy of this year until just before it ended. Can’t imagine what I was so preoccupied with...

What I think I have felt most in the past few months is the strain of standing in the middle of two forces the pandemic has laid bare in education. That fault line runs directly under the intersection of what I appreciate most and least about my job.

The reason I love teaching—like all good teachers I know—is the students. It’s a cliched answer because is so consistently true.

Over the years, I have worked with now thousands (in the plural) of students from elementary kids to doctoral candidates. And I don’t teach large seminars at the college level, so when I say I’ve worked with them, I really have. I have mentored writers, coached basketball players and runners, spent weekends and summers helping some students remediate their grades and others get their books ready for publication.

The headaches in all of this are numerous, but the sense of purpose I gain from helping people engage their work and their lives in ways that push them toward expecting more of themselves is why I do this.

I guess my motivations are pretty basic: tending their growth is what makes me happy. It’s also a site of much learning on my part.

At the same time, the charge toward re-opening schools in the fall despite many strong reasons to resist such plans highlights the thing I can’t find a way to reconcile about my profession.

We’ve made schools a business and it’s wrecked them. And in the process, teachers from Kindergarten to graduate studies have been saddled with duties and expectations that take us from the things we should be focused on: teaching students and partnering with them in the ways they most need.

I know of no other profession that caters more to the desires of people who come from outside of it with no expertise in what makes it work best. Everybody went to school, which apparently makes them an expert, or so the tone of their advice would seem to indicate.

And I get it: there are many stories of schools from tiny districts to large universities failing at their charter. But where that should mean correcting via best practices and the research that exists on the subject, American schools have done what all American institutions do: they’ve applied the thinking of corporate efficiency and capitalistic incentives through resource scarcity to look for ways to “improve” education.

Only to achieve the opposite effect.

We defund higher education. We saddle students with crushing debt. We make teachers perform administrative duties while increasing administrative bloat at every turn. We increase class sizes and demand more work from teachers already overloaded. We pay less and expect more.

We test students into the ground, measuring abstract notions of “development” and “performance” that tell us little more than how well the system was designed to embrace or erase where those students come from.

We spend on campus police and stadiums while cutting back on counselors and support staff. We say we offer a free education in our country without really counting the costs associated with it.

We fund schools by their zip code, thus ensuring those in the wealthiest neighborhoods remain one more source of privilege for the minority of students who can attend them.

And in all of this, we prefer only the stories of the exceptional educators. The ones who teach math in the inner city and suffer a heart attack from the stress. The ones who help students find their own voice in writing, showing their dedication by going bankrupt in the process. The ones who seem heroic by simply learning that it takes more than good intentions to be a good teacher and it was never their job to save these kids in the first place.

We love these teachers because they feed the narrative of exceptionalism. They are also myths.

The reason I love teaching doesn’t come with a casting announcement for who will play me in the movie version of my time in the classroom (though we all know it will be Liev Schreiber). It doesn’t carry cash incentives like selling steak knives. And in most cases, it does not come with the overt recognition of the people around me.

It’s the small moments when students allow us in enough to learn that they are not destined to fail. That they are not invisible. That they are, in fact, capable of more than people have given them credit for, themselves included.

Good teachers make a life’s study of how they can become more human and approachable rather than how they can be more “rigorous” (generally a euphemism for how they can make their preferred style of learning the definition of difficulty in the classroom).

They train for seeing the smallest signs of growth or openness and they press into them rather than seeking to flatten out all the students into one homogeneous set drones who can perform equally under the same expectations.

They don’t work at being popular so much as trustworthy and fair. And they don’t care as much about grades as they do about gradual improvement, even when the system pushes them—hard—to do just the opposite.

And that’s what hit me about my workiversary. I didn’t see it coming because I’m perpetually too busy with that course of study. I’m not perfect. Hell, I’m not even exceptional.

I’m merely reaching for effective. That’s enough, contrary to what the “experts” in everything other than education contend.

Books — A Stranger’s Journey: Race, Identity, and Narrative Craft in Writing

The effect of the whole—which rests on the author’s ability to move between the registers of writer, educator, and theorist—is truly impressive and allows Mura to dispense hard truths without shutting down the potential for writers to commit to doing the work and growing more competent with their representations of people from other backgrounds and life experiences.

As part of my sabbatical, I read widely and by choice, dipping into books I’ve wanted to get to but could not as well as several that came out recently. As part of my post-sabbatical reflections, I’ve written several short but specifically focused responses to some of what I read. These responses, like the one below, focus on one element each from a select list of readings and represent the best of what I encountered.

A Stranger’s Journey: Race, Identity, and Narrative Craft in Writing

David Mura, The University of Georgia Press (2018)

Find the book here. Check out Mura’s website here.

One of the thorniest issues in teaching creative writing, particularly from my position relative to the issue, is exploring how best to create and write about characters of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds than the author.

This is particularly difficult for young white writers who are likely just coming to terms—if they have found those terms at all—with the way their racial designation acts as a pass-through rather than definitional label. This positioning of whiteness as the baseline for cultural expectations often creates assumptions about others’ race and identity that are prone to flattening and stereotyping. And that’s if they acknowledge those other groups at all.

This is why David Mura’s A Stranger’s Journey is such a powerful resource. It explores these issues in direct but applicable ways, identifying issues that cause such assumptive thinking, the barriers to identifying them in ourselves, practicable ways writers can improve, and all while holding writers accountable for engaging this work as diligently as they study elements of craft and voice.

“...[A]s long as white writers unconsciously assume whiteness and the whiteness of their characters as the universal default, both as a literary technique and as an approach to the world, they will almost always fail when they attempt to portray people of color, whether in fiction or in nonfiction” (34).

To delve into this unconscious assumption, Mura cites a raft of writers and thinkers on the subject, compares in parallel the efforts of various writers to convey issues of race and identity, and describes his own process in examinations of writing he has done. And in the process, the work he does with the sources he connects offer a fantastic set of resources readers can mine as they continue exploring perspectives that de-center whiteness.

The effect of the whole—which rests on the author’s ability to move between the registers of writer, educator, and theorist—is truly impressive and allows Mura to dispense hard truths without shutting down the potential for writers to commit to doing the work and growing more competent with their representations of people from other backgrounds and life experiences.

“I am not saying authors can’t cross racial boundaries and write about characters not of their own race. But one can do this in a way that falsifies, simplifies, and fails to portray the complexities of a character of another race—or one can do this in a way that does justice to the reality of that character, that acknowledges the character is complexity and the full nature of his or her reality and experience” (33).

In all, A Stranger’s Journey offers a needed and immanently accessible guide for writers to starting the process of deconstructing our racial assumptions and blind spots for the sake of rebuilding ourselves as better storytellers and people in general.

Injuries, Meaning, and Grafted Essays

All of these bear on the way I see the world and move through it on a daily basis. The remnants of my pains—small and large, physical and psychic—are often the glass between me and my experiences, generally transparent but definitely impacting how I see what I think I’m looking at. And sometimes, the most surprising thoughts come when I take the time to look at the window rather than the view.

If trying to understand our lives is this cloud, the hole where the light shines through is so often opened up by the injuries we experience along the way.

This the fourth installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

As a writer, I find myself pulled between writing multi-voiced fictional stories and multi-concept literary essays. Another way to put it: I don’t make it easy on myself and writing is already difficult enough.

But I am drawn to the narratives found in the spaces between people’s varied accounts of the same events or ideas. I also love when I find connection where there should be disjunction. Maybe it feels like meaning when there shouldn’t be any. Maybe that’s just faith found in another form.

Anyway, one of my creative projects over the sabbatical was planning a series of pieces I’m calling grafted essays that bring together injuries I’ve had over the years and a seemingly disconnected topic or concept. This form has been working its way to the surface of my aesthetic for a while now, as can be seen in this essay I wrote about a terrifying medical moment in my dad’s life and the way it intersected with a realization about my own role as a father.

The challenge of each of these pieces is connecting the reader with the ways in which my view of life is so often bound up in how I’ve been hurt…something I think is fundamentally true for all of us.

This work has been, surprisingly, enjoyable despite that fact that I am dredging up some physically painful experiences and casting a very wide net in looking for complimentary ideas that feel estranged from my personal stories while remaining connected in relevant ways in my head.

That last part is as confusing while I’m working as it was when you read it.

But the process has opened up some perspectives into how much I’m still carrying the injuries I thought I had walked off and how centrally my systems for making sense of the world run through the less-than-conscious remnants of those pains. This was the through line of an essay I wrote about the relative difference in thinking about my own childhood injuries and those of my children, which found a home at Punctuate Magazine.

So, I’ve been spending time in the middle of my most painful moments. The night I tore my ACL and the afternoon it was my hamstring. My bouts of depression and my more than 30 years of regular periods of severe insomnia. Losing my singing voice permanently at 19—which subsequently found print life in The Jabberwock Review—and greeting my 40s with a heart scare.

All of these bear on the way I see the world and move through it on a daily basis. The remnants of my pains—small and large, physical and psychic—are often the glass between me and my experiences, generally transparent but definitely impacting how I see what I think I’m looking at. And sometimes, the most surprising thoughts come when I take the time to look at the window rather than the view.

Sometimes you have to see the dirt before you know what needs to be cleaned, and there’s nothing like writing to highlight where to starting scrubbing.

Books — Heavy

Truly, this is a stunning work of enduring the shadowy spaces where we either make our stories concrete truth in order to preserve a fundamentalist’s certainty of our self-perception or shade our truths with self-preserving fictions because the rawest parts of ourselves are most difficult to look at.

As part of my sabbatical, I read widely and by choice, dipping into books I’ve wanted to get to but could not as well as several that came out recently. As part of my post-sabbatical reflections, I’ve written several short but specifically focused responses to some of what I read. These responses, like the one below, focus on one element each from a select list of readings and represent the best of what I encountered.

Heavy

Kiese Laymon, Scribner (2018)

Find this book here. Check out Laymon’s website here.

I spend my time—writing, reading, and teaching—moving between the ways we consider some stories true and some invention, most often left in the uncomfortable in-between where neither of those descriptors fit because they both apply.

This is likely why Kiese Laymon’s Heavy was such a powerful read when I encountered it. Laymon lays bare his life in a stunning fashion, wrestling with the truths and fictions of growing up Black and male and large in America. Constructed, in some ways, as a letter to his mother, the author frames the entire work in the midst of that contested space, as can be seen in the last lines of the introductory chapter.

“I wanted to write a lie.

You wanted to read that lie.

I wrote this to you instead” (10).

The constant metaphor of the book is weight: physical, spiritual, emotional, and cultural. Sometimes those burdens were visible and others so embedded in his experiences it took years to identify all the ways he’d been carrying them. In some instances they led to stark truth, while in others they birthed inventions required to survive, even as those inventions ate away at him.

Truly, this is a stunning work that lays bare the effort required to endure the shadowy spaces where we either make our stories concrete truth in order to preserve a fundamentalist’s certainty of our self-perception or shade our truths with self-preserving fictions because the rawest parts of ourselves are most difficult to look at.

Resisting both of those impulses, though, is exactly central to Laymon’s efforts in writing Heavy and the dominant preoccupation I carried throughout my reading of his work.

“For the first time in my life, I realized telling the truth was way different from finding the truth, and finding the truth had everything to do with revisiting and rearranging words. Revisiting and rearranging words didn’t only require a vocabulary; it required will, and maybe courage. Revised word patterns were revised thought patterns. Revised thought patterns shaped memory” (86).

This is the benefit of a work like Heavy. It holds us in a posture of attention, both to the weight Laymon carries and our own burdens. But, if we’re attentive and willing, it also forces us to consider the ways we may have weighed on others, intentionally or not. And that is work we all must do.

You mean I HAVE to go to San Diego for research?

To combat the near-constant sense of overwhelmedness I felt, I started charting and mapping my storylines, trying to figure out where all of this was taking me. As you can see in the pictures included with this post, even exerting that level of external on it all left a lot to deal with.

As far as locations that need to be studied go, the hometown is not half bad.

This the third installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

A lot of the work that I was able to accomplish toward my novel was doing extended research on a number of subjects I needed to have pulled together in my mind in order to finally push the story (and the stories that make it up) forward.

Sometime about halfway through May, a friend asked me what I was spending my time learning about and after I listed several of the subjects in my browser tabs and the books I’d read, she looked at me like I was spouting gibberish. I stopped and thought about it outside of the context of my novel and had to laugh.

My research for the novel includes delving into:

· Postal network art;

· Suicide as performance art;

· Podcast production;

· Terminology connected with the creation of eight separate forms of art;

· Security procedures at a decommissioned nuclear reactor;

· Military supply clerking norms and duties;

· Portable barricade technology;

· Police investigative procedure;

· The history of the Hillcrest neighborhood in San Diego;

· Ray Johnson;

· The relative differences between various forms of suicide bombs;

· Remittances;

· Marine recruitment procedures;

· Crime scene photography;

· Currency markets and trading;

· About 30 other topics…

This doesn’t include the trips I took to San Diego so I could walk routes and take pictures of where the characters in my story exist in the moments I depict them. Add to this the overlay of the cultural, spiritual, moral, and regional frameworks of it all as my characters range from a day trader to a high school dropout-turned Marine recruit to a journalist just to name a few. To say there are a lot of moving parts in my head would be a massive understatement.

A key location in my manuscript, in reflection.

Part of a Hillcrest mural that made it onto the page in a later draft.

To combat the near-constant sense of overwhelmedness I felt, I started charting and mapping my storylines, trying to figure out where all of this was taking me. As you can see in the pictures included with this post, even exerting that level of external on it all left a lot to deal with.

With 12 separate first-person perspectives and a shared narrative that absents it’s central figure, some of those charts got complicated pretty quickly.

An early map of the neighborhood where most of the story takes place. Sure, I could have used Maps and dropped pins in various locations. Sure, most of these details have changed. Sure, this is evidence of why I’m not a visual artist. But I wanted a sense of co-creation in these notes.

Graphing paper was really helpful in picturing the exact size and spacing of an important location in the story. This is one of 24 charts of the space I made.

But this work also began to clarify matters I hadn’t been able to get at before. And while I can’t claim I see it all yet, I can see where I’m headed…at least until the next unexpected divergence in the road…

From one of my walking tours of the neighborhood, this seemed like the cliched thing to do.

Books — An American Marriage

But what I am more interested in here is the way in which the setting of this novel is a mute but never voiceless fourth main character. The world is a force bent on the destruction of relationships, forcing Roy, Celestial, and Andre to bear up under its constant, crushing weight.

As part of my sabbatical, I read widely and by choice, dipping into books I’ve wanted to get to but could not as well as several that came out recently. As part of my post-sabbatical reflections, I’ve written several short but specifically focused responses to some of what I read. These responses, like the one below, focus on one element each from a select list of readings and represent the best of what I encountered.

An American Marriage

Tayari Jones, Algonquin Books (2018)

Find the book here. Check out Jones’s website here.

There is a moment early in An American Marriage that frames the entire tragedy of this great novel.

Roy Hamilton, one of the book’s three main characters, has been accused of raping a woman at a motel near his small hometown. Celestial, his wife, knows he could not have committed the crime as they were together in their own room when it happened.

At Roy’s trial, she is called as an eyewitness for the defense and testifies to this effect. Regardless of this, Roy is convicted despite the fact that there is no physical evidence he committed the crime and an eyewitness who could vouch for where he was when the crime occurred.

But none of this truth matters in the opinion of the jury. Reflecting back on the trial, Celestial remembers the moment this way:

“What I know is this: they didn’t believe me. Twelve people and not one of them took me at my word….Even before I stepped down from the witness stand, I knew that I had failed him” (38).

This is the power of An American Marriage, the story of three lives torn apart by the pervasive racial bias and violence against black bodies perpetrated by the American legal system. By all accounts, Roy should have been found innocent and returned to his life of middle class striving in Atlanta.

But, because he is black, the presumption of his guilt supersedes any advantages he may have had and he is sentenced to 12 years in prison. Torn apart, their marriage strains more and more at the seams until Celestial forms a new relationship with her childhood friend Andre (who introduced her to Roy), and all three are forced to weather various ways America is still constructed to destroy black families.

Against this backdrop and in a shared narrative between these three voices, Jones weaves a masterwork of fear and longing and strength and failure. I could spend an entire post on the way she merges a traditional novel format with the epistolary mode of storytelling and a multi-voiced construction so seamlessly and with singular power.

But what I am more interested in here is the way in which the setting of this novel is a mute but never voiceless fourth main character. The world is a force bent on the destruction of relationships, forcing Roy, Celestial, and Andre to bear up under its constant, crushing weight.

Their efforts are imperfect and the ending is anything but neat as Roy is released and tries to reconcile with Celestial—the hope of which kept him alive in prison—only to discover she and Andre have grown together in his absence. But they are real humans in the face of great inhumanities.

The fact that they survive is a testament to their strength. The fact that they have to is a testament to our great weakness as a society.

This novel is an open question regarding whether or not we will ever look long enough at the stories that could show us how badly we need to change.

A novel concept that needs to be a novel

And in the end, is it done? Of course not. It’s drafted, mostly, and the rest of the stories that aren’t quite there are in process. I think it might actually happen if the sprint that is teaching my classes doesn’t completely derail my progress…which it might. *Narrator’s Voice* It did indeed derail that progress.

This the second installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

One of many charts and diagrams I’ve created over the years trying to get an handle on this novel.

The whole point of my sabbatical, on paper anyway, was completing a novel that has been eluding me for close to eight years now. The problem: the sabbatical application that goal was written down on committed me to actually finishing the thing.

About that…

I first had the idea for the story when I was teaching in San Diego. It’s sprawling and complicated.

Twelve independent voices collectively telling the story without the main character every getting her own chance to do so.

A major incident around which the entire story is built, but that never gets expressed directly on the page.

A secondary story that may or may not draw all the threads—material and metaphysical—together as a coherent singular.

The small question of why bad things happen and whether or not that is even a possible outcome in asking questions about those bad things in the first place.

And doing justice to my hometown that is so often invisible on the literary landscape.

No pressure. But I had six months and a mandate…yeah…no pressure at all.

And in the end, is it done? Of course not. It’s drafted, mostly, and the rest of the stories that aren’t quite there are in process. I think it might actually happen if the sprint that is teaching my classes doesn’t completely derail my progress…which it might. *Narrator’s Voice* It did indeed derail that progress.

I needed the sabbatical because of that barrier in the first place. The problem, though, was that other barriers, good and bad, sprang up in my time away and I’m not where I wanted to be on the story. It’s not ready for others to read what I’ve come up with so I can refine it and get serious about looking for a publisher.

But I’m close. Closer than I’ve ever been with this story. I have hope. Maybe that was the best possible outcome of the sabbatical because before I took it, I was starting to lose any sense of every getting this book done.

Or the three other ideas I have behind it.

Or so the song goes.

What we don’t do about those divisions might just be our defining characteristic as a nation.

Photo by Mohammad Metri on Unsplash

My essay, “On small towns, protests, and backs turned…” relies heavily on lyrics from nine songs that punctuate the end of each of its sections. Some are ironic, some directly connected, but all coalesce around a particular thread in my thinking.

All of these songs end up—intentionally or unintentionally—focused on the divides between us.

What we don’t do about those divisions might just be our defining characteristic as a nation.

“Devil Inside” by INXS

“Small Town” by John Mellencamp

“For What It’s Worth” by Buffalo Springfield

“Hell You Talmbout” by Janelle Monae and Wondaland Records

“Silence” by PJ Harvey

“Biko” by Peter Gabriel

“Know Your Rights” by The Clash

“Under Pressure” by Queen and David Bowie

“Behind the Wall” by Tracy Chapman

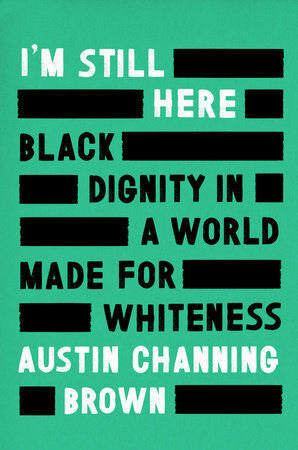

Books — I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Still Made for Whiteness

That makes this a book a service and gift to white readers Brown was not obligated to provide us.

As part of my sabbatical, I read widely and by choice, dipping into books I’ve wanted to get to but could not as well as several that came out recently. As part of my post-sabbatical reflections, I’ve written several short but specifically focused responses to some of what I read. These responses, like the one below, focus on one element each from a select list of readings and represent the best of what I encountered.

I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Still Made for Whiteness

Austin Channing Brown, Convergent Books (2018)

Find the book here. Visit Brown’s website here. And check out her show The Next Question here.

Before I read I’m Still Here, I caught an interview with author Austin Channing Brown on the Seminary Dropout podcast that opened with her recounting how her parents named her Austin as a way of preventing people from responding to her out of their prejudices before they’d actually met her.

This, of course, collapsed for her when a librarian looked at her name on a library card and said it couldn’t be hers. And there it was: regardless of how Black people attempt to engage or adopt dominant, normalized notions of white culture, they end up excluded because that is the nature of white supremacy.

Sadly, as Brown’s book describes in various settings, this is exactly the way that Evangelical organizations end up treating Black people who have been invited in, ostensibly, to address the very issue of lacking diversity. This sad irony is distilled in the following passage:

In this way whiteness reveals its true desire for people of color. Whiteness wants us to be empty, malleable, so that it can shape Blackness into whatever is necessary for the white organization’s own success. It sees potential, possibility, a future where Black people could share some of the benefits of whiteness if only we try hard enough to mimic it….Rare is the ministry praying that they would be worthy of the giftedness of Black minds and hearts (79).

This insight, in my opinion, is critical both in Brown’s decision to stop playing the diversity game by rules that maintain the status quo and for reshaping the issue for those of us who may not understand how our choices are exactly what keep those rules in place in the first place.

The starkest racial divides often exist in spaces so deeply ingrained in the systems and thinking operating so seamlessly in white culture that they’ve been rendered invisible. They manifest only in the erasure of Black people.

By nature, this erasure of others also sweeps away the very traces of its existence in the eyes of those who benefit from it. This requires marginalized people to choose: do they continue to conform or do they resist in an attempt to be rendered visible despite all the potential costs that come with that resistance?

I’m Still Here, then, is the story of Brown’s path to claiming her own space by stepping outside environments that made her have to ask to be seen in the first place. It’s also her moment of pivoting away from trying to create messages for a predominantly white audience who aren’t listening in ways that enable hearing they’re being told.

That makes this a book a service and gift to white readers Brown was not obligated to provide us. To read it as anything else is a vestige of a power structure that demands every message must protect the sensibilities of a group that actually needs to see and feel the pain we cause others—as much as it is possible for us to do so—in order to understand our need to change.

Note: This book made the New York Times Bestseller List this week, and rightfully so.

“So you got want you wanted…”

No, the point of my solo hike through my own interests was to see just how estranged I’d become from what matters to me in the day-to-day of my teaching. When I slowed down and looked around, I realized I wasn’t doing what makes me a better than decent instructor. I wasn’t doing.

At the beginning of my sabbatical, I laid out this daily calendar and filled my days with plans for what would do. Let’s just say that was a touch optimistic.

This the first installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

Traditionally, academics are eligible for sabbaticals every seven years or so. The practice, ostensibly, is to set aside a time for scholars to renew their studies, pursue projects that teaching does not allow them to focus on solely, and to recharge for their work in the classroom.

Put another way, it’s not a vacation. It’s a time for the work that’s usually fit in around the edges of the myriad shifting commitments be teaching and facilitating the business of the academy.

It’s also a phenomenal opportunity to choose what you want to work on along with how and when you will do that work. It is, as I said when I received my confirmation letter, the Golden Ticket. Truly, it’s something most writers never get and not a privilege I take lightly.

Which means it’s also a lot of pressure.

When I applied for the time away, I said I wanted to finish a novel that has been eluding me for eight years. I was also “encouraged” to complete an academic task of creating an annotated bibliography regarding literacies in digital literature, a field I find myself increasingly working within.

Spoiler alert: neither of those projects is done.

Double spoiler: I’m totally fine with that, even with the fact that the bibliography will likely never be done at all.

Completion just wasn’t the theme of my sabbatical, even as I completed a ton of work. Wrote more than 100,000 words and finally—maybe—figured out that novel.

No, the point of my solo hike through my own interests was to see just how estranged I’d become from what matters to me in the day-to-day of my teaching. When I slowed down and looked around, I realized I wasn’t doing what makes me a better than decent instructor. I wasn’t doing.

This isn’t to say that the lack of total progress didn’t (or doesn’t) bother me at all. I actually had to wait closer to nine years for my first chance at sabbatical, so I felt extra pressure to perform, feelings exacerbated by my Type-A tendencies toward workaholism.

Factor in some bouts of depression and a number of unplanned but unexpectedly great projects landing in my lap over that time and there was a lot of being forced to adjust my expectations, not just for what I would accomplish on sabbatical, but in how I need to live now that I’m back. How I need to appreciate what I do complete. What I need to cut loose from my perceived load of responsibilities.

That last part is a work in progress, but the change is set in me, and I believe that is for the best.

The following series of posts, then, is an accounting of the specifics of that season—delayed six months by the trivial matter of a global pandemic—and the changes it created. It’s not a justification, though. I’ve done enough of that in my life.

Like everything else I’m interested in, it’s a story and one that needs telling, if only for my own clarity and to serve as a reminder that I’ll be doing this thing differently from here on out.