WRITING AFTER SUNSETS

For years, I maintained a separate blog called writing after sunsets as a place for my thoughts on writing, reflections on teaching, and an outlet for writing that matters to me in ways that make me want to control how it is published. It has also been, from time to time, a platform for the work of others I know who have something to say.

Now, with this site as my central base of online operations, I’m folding that blog into the rest of my efforts. All previous content is here for easier access, but the heart of writing after sunsets remains in both my earlier posts and those to come.

I’m editing a book? I’m editing a book.

Part editor, part encourager, I spent the summer working the book through with her, reminding her over and over that these were, indeed, stories y’all need to hear. Stories she needed to tell.

In many ways, I watched this book grow up. And now that it’s out, it should be on your shelves. Find it here and read it as soon as you can. It matters that much.

This the sixth installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

As I’ve noted in my post last Wednesday, there were a couple of major projects I’d not planned on doing that appeared out of the sabbatical ether, one of which is very special to me.

So often in my role as a professor of writing, I am in the position of helping younger writers launch big projects they will most likely complete well after they’ve finished school, if they ever find an end to those projects at all. Well after they are no longer my student or someone I see regularly.

These ideas are usually rough, vastly more expansive than any one story or even book can effectively express, and often not even actually the project the writer wants to tackle in the end.

Shorter: I’m often helping with the heaviest lifting in the writing process, the winnowing.

Sometimes, however, writers come to me with a concept that is ready to press forward immediately; a project with a sense of itself; a message in need of an audience as much as an editor or creative consultant.

Such was the case with Kathryn’s work. When she was a senior in our undergraduate program and a member of my advanced creative writing class, she stopped by my podium on the way out one evening and asked if I would read an essay of hers that had recently been published. I knew her as an avid reader and, primarily, as an author of science fiction, so I was curious to see what she cared about in nonfiction.

Note: please visit her author site, Speak the Write Language, and find her publication list. She’s prolific, gifted in all phases of writing, and a voice you should hear from.

So, of course I said yes, read it a couple days later, and immediately told her it was fantastic. Because it was, and is, as you will see in the version that made it into her book. I also told Kathryn that it felt like she had more to say in essay form.

And then the term ended and Kathryn graduated and for a while we touched base at church from time to time, not really finding space to talk about her essays in any substantive form. A couple years later, she ended up back in my classroom—this time in the M.A. program—and she told me that she had, indeed, more to say. Had done a lot of growing. Needed to respond to the first essay she’d shown me because she didn’t see the world in quite the way she did back then.

She asked if I would chair her capstone committee and work with her on creating a collection of essays on growing increasingly aware of what it is to be black and a woman in an America that is not and may never be capable of becoming post-racial.

Six months of work and what at the time seemed like four-ish essays later, the infant version of what would become Black Was Not a Label came into being. It was, even in its still-developing form at the time, stunning. An associate dean who reads all the graduate projects before they are approved pulled me aside at an end of the year event and said, “These are stories that people need to read.”

I agreed and encouraged Kat think about expanding the collection by a few more essays and then look for a publisher. It was that good. Then she graduated. Continued working as a freelance writer. Took an internship at a local publisher to consider a job in the industry. Submitted a couple places.

You know, generally lived the life of an emerging writer with all its potentials and frustrations.

Then came the ebullient message. A new publisher had read her manuscript. Had offered a contract. Had allowed her input on who should get to help prep the book for publication. And Kathryn thought of me.

I said yes, slid a couple projects to the side (one likely permanently) and jumped in. The work was in the small matters. The turns of phrase. The transitions from idea to idea. The order of the pieces toward a more cohesive pathway that leads to a singular read of the many (now almost eleven) parts.

Part editor, part encourager, I spent the summer working the book through with her, reminding her over and over that these were, indeed, stories y’all need to hear. Stories she needed to tell.

Kathryn and I at her book launch, an event I was honored to help facilitate.

In August, when my part of the work was done, I took one last pass over the document, reading it as part of the audience for the first time. Then I wrote my editor’s note that is now included the book. It seems a fitting way to close this post.

This is book of echoes, at once a path through a pain-shrouded past and a map toward a future where healing is possible. But first, as Kathryn tells both versions of herself in “Erasure,” we must look at what we have been too afraid to examine. We must slow down and consider the wounds, opened and reopened for centuries, that create the world where these words were framed and formed. We must listen with no other intent but to grieve and allow that sadness to reshape us.

There was a moment in the editing process when, like stopping on a long hike to look back on the expanse of trail one has covered, I paused to reflect on the scope of the work being done in these pages. Rather, I was brought up short by these lines:

“…but this is not helplessness. It is weight. I sit constant beneath the knowledge that there is little to be done—that to try would be to strain against centuries upon centuries of strivings turned to death turned to mourning turned to moaning ghosts hurling their laments from the broken boughs of ancient trees.”

Black Was Not a Label is a reckoning of the most intimate nature, one that demands—gently but persistently—to be read more than once. The first passage through these lines is personal, a shared space between you and the author’s experiences. But the return trip is where you will begin to hear the call and response of these separate passages now collected as one volume. Pay attention to the way these words move like spirits to connect the weight and strain of our past to move through soul-deep hurt toward a hope that remains even still.

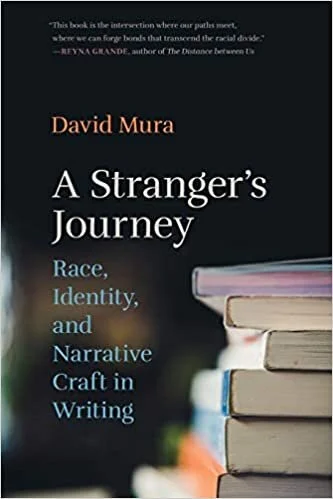

Books — A Stranger’s Journey: Race, Identity, and Narrative Craft in Writing

The effect of the whole—which rests on the author’s ability to move between the registers of writer, educator, and theorist—is truly impressive and allows Mura to dispense hard truths without shutting down the potential for writers to commit to doing the work and growing more competent with their representations of people from other backgrounds and life experiences.

As part of my sabbatical, I read widely and by choice, dipping into books I’ve wanted to get to but could not as well as several that came out recently. As part of my post-sabbatical reflections, I’ve written several short but specifically focused responses to some of what I read. These responses, like the one below, focus on one element each from a select list of readings and represent the best of what I encountered.

A Stranger’s Journey: Race, Identity, and Narrative Craft in Writing

David Mura, The University of Georgia Press (2018)

Find the book here. Check out Mura’s website here.

One of the thorniest issues in teaching creative writing, particularly from my position relative to the issue, is exploring how best to create and write about characters of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds than the author.

This is particularly difficult for young white writers who are likely just coming to terms—if they have found those terms at all—with the way their racial designation acts as a pass-through rather than definitional label. This positioning of whiteness as the baseline for cultural expectations often creates assumptions about others’ race and identity that are prone to flattening and stereotyping. And that’s if they acknowledge those other groups at all.

This is why David Mura’s A Stranger’s Journey is such a powerful resource. It explores these issues in direct but applicable ways, identifying issues that cause such assumptive thinking, the barriers to identifying them in ourselves, practicable ways writers can improve, and all while holding writers accountable for engaging this work as diligently as they study elements of craft and voice.

“...[A]s long as white writers unconsciously assume whiteness and the whiteness of their characters as the universal default, both as a literary technique and as an approach to the world, they will almost always fail when they attempt to portray people of color, whether in fiction or in nonfiction” (34).

To delve into this unconscious assumption, Mura cites a raft of writers and thinkers on the subject, compares in parallel the efforts of various writers to convey issues of race and identity, and describes his own process in examinations of writing he has done. And in the process, the work he does with the sources he connects offer a fantastic set of resources readers can mine as they continue exploring perspectives that de-center whiteness.

The effect of the whole—which rests on the author’s ability to move between the registers of writer, educator, and theorist—is truly impressive and allows Mura to dispense hard truths without shutting down the potential for writers to commit to doing the work and growing more competent with their representations of people from other backgrounds and life experiences.

“I am not saying authors can’t cross racial boundaries and write about characters not of their own race. But one can do this in a way that falsifies, simplifies, and fails to portray the complexities of a character of another race—or one can do this in a way that does justice to the reality of that character, that acknowledges the character is complexity and the full nature of his or her reality and experience” (33).

In all, A Stranger’s Journey offers a needed and immanently accessible guide for writers to starting the process of deconstructing our racial assumptions and blind spots for the sake of rebuilding ourselves as better storytellers and people in general.

Injuries, Meaning, and Grafted Essays

All of these bear on the way I see the world and move through it on a daily basis. The remnants of my pains—small and large, physical and psychic—are often the glass between me and my experiences, generally transparent but definitely impacting how I see what I think I’m looking at. And sometimes, the most surprising thoughts come when I take the time to look at the window rather than the view.

If trying to understand our lives is this cloud, the hole where the light shines through is so often opened up by the injuries we experience along the way.

This the fourth installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

As a writer, I find myself pulled between writing multi-voiced fictional stories and multi-concept literary essays. Another way to put it: I don’t make it easy on myself and writing is already difficult enough.

But I am drawn to the narratives found in the spaces between people’s varied accounts of the same events or ideas. I also love when I find connection where there should be disjunction. Maybe it feels like meaning when there shouldn’t be any. Maybe that’s just faith found in another form.

Anyway, one of my creative projects over the sabbatical was planning a series of pieces I’m calling grafted essays that bring together injuries I’ve had over the years and a seemingly disconnected topic or concept. This form has been working its way to the surface of my aesthetic for a while now, as can be seen in this essay I wrote about a terrifying medical moment in my dad’s life and the way it intersected with a realization about my own role as a father.

The challenge of each of these pieces is connecting the reader with the ways in which my view of life is so often bound up in how I’ve been hurt…something I think is fundamentally true for all of us.

This work has been, surprisingly, enjoyable despite that fact that I am dredging up some physically painful experiences and casting a very wide net in looking for complimentary ideas that feel estranged from my personal stories while remaining connected in relevant ways in my head.

That last part is as confusing while I’m working as it was when you read it.

But the process has opened up some perspectives into how much I’m still carrying the injuries I thought I had walked off and how centrally my systems for making sense of the world run through the less-than-conscious remnants of those pains. This was the through line of an essay I wrote about the relative difference in thinking about my own childhood injuries and those of my children, which found a home at Punctuate Magazine.

So, I’ve been spending time in the middle of my most painful moments. The night I tore my ACL and the afternoon it was my hamstring. My bouts of depression and my more than 30 years of regular periods of severe insomnia. Losing my singing voice permanently at 19—which subsequently found print life in The Jabberwock Review—and greeting my 40s with a heart scare.

All of these bear on the way I see the world and move through it on a daily basis. The remnants of my pains—small and large, physical and psychic—are often the glass between me and my experiences, generally transparent but definitely impacting how I see what I think I’m looking at. And sometimes, the most surprising thoughts come when I take the time to look at the window rather than the view.

Sometimes you have to see the dirt before you know what needs to be cleaned, and there’s nothing like writing to highlight where to starting scrubbing.

You mean I HAVE to go to San Diego for research?

To combat the near-constant sense of overwhelmedness I felt, I started charting and mapping my storylines, trying to figure out where all of this was taking me. As you can see in the pictures included with this post, even exerting that level of external on it all left a lot to deal with.

As far as locations that need to be studied go, the hometown is not half bad.

This the third installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

A lot of the work that I was able to accomplish toward my novel was doing extended research on a number of subjects I needed to have pulled together in my mind in order to finally push the story (and the stories that make it up) forward.

Sometime about halfway through May, a friend asked me what I was spending my time learning about and after I listed several of the subjects in my browser tabs and the books I’d read, she looked at me like I was spouting gibberish. I stopped and thought about it outside of the context of my novel and had to laugh.

My research for the novel includes delving into:

· Postal network art;

· Suicide as performance art;

· Podcast production;

· Terminology connected with the creation of eight separate forms of art;

· Security procedures at a decommissioned nuclear reactor;

· Military supply clerking norms and duties;

· Portable barricade technology;

· Police investigative procedure;

· The history of the Hillcrest neighborhood in San Diego;

· Ray Johnson;

· The relative differences between various forms of suicide bombs;

· Remittances;

· Marine recruitment procedures;

· Crime scene photography;

· Currency markets and trading;

· About 30 other topics…

This doesn’t include the trips I took to San Diego so I could walk routes and take pictures of where the characters in my story exist in the moments I depict them. Add to this the overlay of the cultural, spiritual, moral, and regional frameworks of it all as my characters range from a day trader to a high school dropout-turned Marine recruit to a journalist just to name a few. To say there are a lot of moving parts in my head would be a massive understatement.

A key location in my manuscript, in reflection.

Part of a Hillcrest mural that made it onto the page in a later draft.

To combat the near-constant sense of overwhelmedness I felt, I started charting and mapping my storylines, trying to figure out where all of this was taking me. As you can see in the pictures included with this post, even exerting that level of external on it all left a lot to deal with.

With 12 separate first-person perspectives and a shared narrative that absents it’s central figure, some of those charts got complicated pretty quickly.

An early map of the neighborhood where most of the story takes place. Sure, I could have used Maps and dropped pins in various locations. Sure, most of these details have changed. Sure, this is evidence of why I’m not a visual artist. But I wanted a sense of co-creation in these notes.

Graphing paper was really helpful in picturing the exact size and spacing of an important location in the story. This is one of 24 charts of the space I made.

But this work also began to clarify matters I hadn’t been able to get at before. And while I can’t claim I see it all yet, I can see where I’m headed…at least until the next unexpected divergence in the road…

From one of my walking tours of the neighborhood, this seemed like the cliched thing to do.

A novel concept that needs to be a novel

And in the end, is it done? Of course not. It’s drafted, mostly, and the rest of the stories that aren’t quite there are in process. I think it might actually happen if the sprint that is teaching my classes doesn’t completely derail my progress…which it might. *Narrator’s Voice* It did indeed derail that progress.

This the second installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

One of many charts and diagrams I’ve created over the years trying to get an handle on this novel.

The whole point of my sabbatical, on paper anyway, was completing a novel that has been eluding me for close to eight years now. The problem: the sabbatical application that goal was written down on committed me to actually finishing the thing.

About that…

I first had the idea for the story when I was teaching in San Diego. It’s sprawling and complicated.

Twelve independent voices collectively telling the story without the main character every getting her own chance to do so.

A major incident around which the entire story is built, but that never gets expressed directly on the page.

A secondary story that may or may not draw all the threads—material and metaphysical—together as a coherent singular.

The small question of why bad things happen and whether or not that is even a possible outcome in asking questions about those bad things in the first place.

And doing justice to my hometown that is so often invisible on the literary landscape.

No pressure. But I had six months and a mandate…yeah…no pressure at all.

And in the end, is it done? Of course not. It’s drafted, mostly, and the rest of the stories that aren’t quite there are in process. I think it might actually happen if the sprint that is teaching my classes doesn’t completely derail my progress…which it might. *Narrator’s Voice* It did indeed derail that progress.

I needed the sabbatical because of that barrier in the first place. The problem, though, was that other barriers, good and bad, sprang up in my time away and I’m not where I wanted to be on the story. It’s not ready for others to read what I’ve come up with so I can refine it and get serious about looking for a publisher.

But I’m close. Closer than I’ve ever been with this story. I have hope. Maybe that was the best possible outcome of the sabbatical because before I took it, I was starting to lose any sense of every getting this book done.

Or the three other ideas I have behind it.

“So you got want you wanted…”

No, the point of my solo hike through my own interests was to see just how estranged I’d become from what matters to me in the day-to-day of my teaching. When I slowed down and looked around, I realized I wasn’t doing what makes me a better than decent instructor. I wasn’t doing.

At the beginning of my sabbatical, I laid out this daily calendar and filled my days with plans for what would do. Let’s just say that was a touch optimistic.

This the first installment of a series reflecting on a sabbatical that ended one year ago. It will run each Wednesday through the summer.

Traditionally, academics are eligible for sabbaticals every seven years or so. The practice, ostensibly, is to set aside a time for scholars to renew their studies, pursue projects that teaching does not allow them to focus on solely, and to recharge for their work in the classroom.

Put another way, it’s not a vacation. It’s a time for the work that’s usually fit in around the edges of the myriad shifting commitments be teaching and facilitating the business of the academy.

It’s also a phenomenal opportunity to choose what you want to work on along with how and when you will do that work. It is, as I said when I received my confirmation letter, the Golden Ticket. Truly, it’s something most writers never get and not a privilege I take lightly.

Which means it’s also a lot of pressure.

When I applied for the time away, I said I wanted to finish a novel that has been eluding me for eight years. I was also “encouraged” to complete an academic task of creating an annotated bibliography regarding literacies in digital literature, a field I find myself increasingly working within.

Spoiler alert: neither of those projects is done.

Double spoiler: I’m totally fine with that, even with the fact that the bibliography will likely never be done at all.

Completion just wasn’t the theme of my sabbatical, even as I completed a ton of work. Wrote more than 100,000 words and finally—maybe—figured out that novel.

No, the point of my solo hike through my own interests was to see just how estranged I’d become from what matters to me in the day-to-day of my teaching. When I slowed down and looked around, I realized I wasn’t doing what makes me a better than decent instructor. I wasn’t doing.

This isn’t to say that the lack of total progress didn’t (or doesn’t) bother me at all. I actually had to wait closer to nine years for my first chance at sabbatical, so I felt extra pressure to perform, feelings exacerbated by my Type-A tendencies toward workaholism.

Factor in some bouts of depression and a number of unplanned but unexpectedly great projects landing in my lap over that time and there was a lot of being forced to adjust my expectations, not just for what I would accomplish on sabbatical, but in how I need to live now that I’m back. How I need to appreciate what I do complete. What I need to cut loose from my perceived load of responsibilities.

That last part is a work in progress, but the change is set in me, and I believe that is for the best.

The following series of posts, then, is an accounting of the specifics of that season—delayed six months by the trivial matter of a global pandemic—and the changes it created. It’s not a justification, though. I’ve done enough of that in my life.

Like everything else I’m interested in, it’s a story and one that needs telling, if only for my own clarity and to serve as a reminder that I’ll be doing this thing differently from here on out.