A Roadmap or a Vacuum

I teach writing. Even when I'm teaching literature, I'm teaching how it was written as a way of seeing why it matters. Words matter to me, because they're never—never—just words.

A simple message of hearing and speaking critically is this: never view rhetoric as empty. How people argue their point is never merely an intellectual construct. It's a roadmap or it's a vacuum.

When you line up what people believe with why they believe it, you get one of those two possibilities in terms of how you can assess where their thinking will take them. Remember, words are never just words.

In some cases, you can see how an argument will play out in action. The sources and, often, the fallacies an arguer draws on to claim authority carry in them behaviors and message shapes the careful listener will find instructive in anticipating where this will go.

Hence: roadmap.

Example: Your friend tells you about a time a person of differing political views tore up a political sign they had posted in their yard. Your friend then points you to four separate Facebook posts describing similar behavior from "the same type" of people and, without pause, uses that in addition to their own experience to characterize all people they suspect as holding even similar political leanings as (fill in the negative characterization most employed by your friends/family/neighbors).

This, as we say in the business, is a fallacious two-fer. The first is the logical mistake of extending one's own personal experience too broadly in relation to the complexity and diversity of experiences found even in the limited world of yard sign destruction. Your friend's story becomes broad proof of their own feelings about "those people."

But everyone, even the most stubborn individualists, know their story isn't enough. Thus the second fallacy—a carefully cultivated mechanism for bias confirmation—becomes important. By linking to a few other friendly examples/perspectives, their own assertions are validated exponentially (in their heads, anyway). And that gives the confidence in their sweeping (and almost always wrong) generalizations-as-facts views.

And this becomes your map. This person will make their own opinions a truth stretched across an issue and act accordingly. It doesn't always tell you what they will do, merely how they will justify themselves after the fact (and yes, that is as scary to type as it is to consider in practice).

But a map is always better than the other option: the vacuum.

Taking the same sign vandalism, the vacuum rhetorician tells you the story and says, "That was wrong, the people who did it are bad, and I will never trust them again." And that's it; they've built a solid wall of certainty you can't see through to their reasoning.

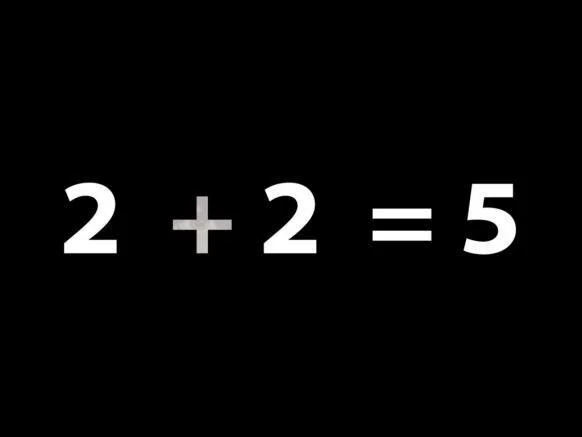

These are not logical structures, they are the results of submerged processes that could hinge on all forms of fallacy or irrationality or even deep bias. But who knows, because this is the rhetorical equivalent of a kid responding to a math problem without showing his work. Right or wrong, you have no idea how that kid ended up where he did.

That's the vacuum. In terms of a math problem, it's confusing and counterproductive. In terms of the sign vandalism, it's problematic.

In terms of where we are in America today, it's terrifying.