On the Death of Rashaan Salaam

The news came in a text first. Then a couple tweets filtered into my timeline, the first from ESPN’s Adam Schefter.

Rashaan’s dead. I guess as you get older, these moments happen more often. Mortality does not discriminate, and when someone like him dies, the rest of us, if we’re paying attention, take personal stock. At least for a moment.

When I say “someone like” Rashaan, I think that’s what’s kept him on my mind for the last 24 hours. I’m not going to claim we knew each other more than we did, which was to say we had a passing acquaintance as guys who ran track in the same league, though by virtue of talent, that league was not actually the same.

The most extensive conversation I can remember having with the guy was about the relative merits of the song “Check the Rhime” on A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory while we waited for a race to get called.

The thing is, Rashaan exists in a weird space between someone I knew and a hero, two boxes I would never place him in. Rather, he exists between, a shining satellite I came into orbit with simply because we ran that same races. That seems to be the case for many people trying to make sense of how he died.

He was neither my peer, nor my nemesis (that honor is taken by a guy named Ron Allen). No, I’d have had to have been faster for that to be the case. Because Rashaan was fast. Really fast. But that’s not the part of his story that gets told.

In the pre-internet world of the early 90s, Rashaan was an eight-man football phenomenon who drew national attention without the aid of YouTube, Vine, or the high school scouting apparatus that exists now. And it was warranted. Dude was crazy.

In a game against my high school, he ran a sweep to the left and one of our best players hit him perfectly below the knees, kicking his feet up over his head. Normal runners are happy not to have been injured by a hit like that. Rashaan put his free hand on the ground like he was doing a handstand, swung his legs back underneath himself, landed on his feet, and ran another 30 yards on the play.

What?

And that was not atypical. But I didn’t play football. So, when he went from tiny La Jolla Country Day to the University of Colorado Boulder to the Heisman Trophy to the Chicago Bears in the first round of the NFL draft, I watched as I had in high school: impressed to have seen him in person but not quite a fan, because he played for the other team.

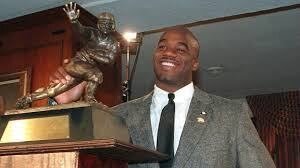

Rashaan with the hardware. Image from ESPN.

Lost in the high school football legend and the perception of his unfulfilled pro potential is the fact that Rashaan could fly on the track. He wasn’t a pretty sprinter, like Carl Lewis or Usain Bolt. He ran like that yoked-up guy on the field, just faster without the pads to slow him down, as if he needed the unencumbering.

If he hadn’t been running in San Diego, in the early 90s, he’d have been touted as one of the fastest guys in his region. Unfortunately for him (and more so for me), that stretch from 1990 to 1998 was a golden age for high school sprinters in San Diego.

For a little context, Rashaan ran a 10.8-10.7 second 100 meter dash. That’s blazing. That kind of high school speed translates to a Division 1 scholarship for many runners (and could have for him had he wanted to focus on track). But that made him one of the second-tier runners when it came to the guys around him.

Guys like Darnay Scott (10.77), Johnny Robinson (10.77), Paul Turner (10.49), and Vince Williams (who would go 10.45 in 1996) all prevented him from being seen as a premier sprinter, not to mention the six other guys in the section running under 11 seconds I haven't named. And then there was Riley Washington, who still holds the CIF state meet record with his ridiculous 10.3 obliteration of the previous mark and the seven fastest guys in California not named Riley.

San Diego was home to several high schools that seemed like speed factories when I was coming up—Morse, Kearny, Lincoln Prep, Southwest, El Camino to name a few—so Rashaan’s freaky speed was, well, kinda ordinary in an extraordinary era. To get a sense of this, check out the 1991 state 200 meter final here, with Darnay and Riley in the race NOT winning.

But let me assure you, there’s looking at a runner’s time on paper, there’s watching them stop the watch on the screen, and then there’s the peculiar sense of having that speed imposed on you by someone who’s just gifted in ways you are not. That’s my clearest memory of Rashaan Salaam.

A brief bit of history, when Rashaan was a junior and I was a sophomore, I ended up running the open 400 against him at a meaningless dual meet . For the first 250 meters, it was very much like he was running and I was barely moving. But I’m fairly certain he was not training for the 400 at that point and he broke down physically, hitting what runners call the wall not once or twice, but three times, allowing me to reel him in and cross the line in a virtual tie.

Reminder: This was a meaningless meet. He would still go on to win the Heisman. I would never reach the CIF meet in the open 100 (his race). I only slightly celebrated in the moment, knowing that if he had cared at all or put in any time training, he would have smoked me. Then I forgot about it.

Apparently, he did not.

The next season we ended up in the same heat of my race, the 200 meter dash. As a junior, I was running just outside fast enough to make the open field at CIF sectionals, but just inside fast enough to end up in races with guys like Rashaan and Darnay. It was, as I’m sure you can imagine, not good for the ego.

This was the first time Rashaan and I had run against each other since the 400 the season before. What happened, I’ve never forgotten.

Rashaan started in lane two while I was in five, which meant I had a stagger of several meters when the gun went off. Also, I was stronger at the tactical thinking of running the curve than the brute speed of the straightaway. And, for once, I came out of the blocks quickly, which was unusual given my relatively tall 6’3” frame.

None of that mattered. The moment I was up and running, all I could hear was the sound of Rashaan’s feet striking the track once for every two strides of mine and his grunting with each footfall. He made up the stagger in the first 20 meters and THEN put the hammer down, rolling past me like I wasn’t even trying. It felt like he picked up a stride on me for every two I took, and no amount of digging deeper made any difference. With 50 meters to go, he was so far ahead he could have jogged the rest of the way.

I wish he had.

Instead, with 20 meters left, he turned and ran backwards, staring at me all the way through the finish line. I crossed about a half of a second later, but it might as well have been a year. I swear, it felt like he had time to pop a soda before I got there.

And that was it. No handshake or high-five or acknowledgement of any kind beyond the utter thrashing he gave me on the track. I only ever saw him again in the 4x100 relay (which we won). And then he was swallowed, by football first, and time after that. I hadn’t really thought about him much recently save on the rare occasions I ended up reliving my track days with old friends.

At least, that was true until yesterday, when they found his body in a park in the Boulder area, the one place he seemed to have been happy, or so I’ve read.

That’s the thing about guys like Rashaan. All we really know about them is left in that 21-second race, a quarter century ago.