WRITING AFTER SUNSETS

For years, I maintained a separate blog called writing after sunsets as a place for my thoughts on writing, reflections on teaching, and an outlet for writing that matters to me in ways that make me want to control how it is published. It has also been, from time to time, a platform for the work of others I know who have something to say.

Now, with this site as my central base of online operations, I’m folding that blog into the rest of my efforts. All previous content is here for easier access, but the heart of writing after sunsets remains in both my earlier posts and those to come.

A Roadmap or a Vacuum

I teach writing. Even when I'm teaching literature, I'm teaching how it was written as a way of seeing why it matters. Words matter to me, because they're never—never—just words.

A simple message of hearing and speaking critically is this: never view rhetoric as empty. How people argue their point is never merely an intellectual construct. It's a roadmap or it's a vacuum.

When you line up what people believe with why they believe it, you get one of those two possibilities in terms of how you can assess where their thinking will take them. Remember, words are never just words.

In some cases, you can see how an argument will play out in action. The sources and, often, the fallacies an arguer draws on to claim authority carry in them behaviors and message shapes the careful listener will find instructive in anticipating where this will go.

Hence: roadmap.

Example: Your friend tells you about a time a person of differing political views tore up a political sign they had posted in their yard. Your friend then points you to four separate Facebook posts describing similar behavior from "the same type" of people and, without pause, uses that in addition to their own experience to characterize all people they suspect as holding even similar political leanings as (fill in the negative characterization most employed by your friends/family/neighbors).

This, as we say in the business, is a fallacious two-fer. The first is the logical mistake of extending one's own personal experience too broadly in relation to the complexity and diversity of experiences found even in the limited world of yard sign destruction. Your friend's story becomes broad proof of their own feelings about "those people."

But everyone, even the most stubborn individualists, know their story isn't enough. Thus the second fallacy—a carefully cultivated mechanism for bias confirmation—becomes important. By linking to a few other friendly examples/perspectives, their own assertions are validated exponentially (in their heads, anyway). And that gives the confidence in their sweeping (and almost always wrong) generalizations-as-facts views.

And this becomes your map. This person will make their own opinions a truth stretched across an issue and act accordingly. It doesn't always tell you what they will do, merely how they will justify themselves after the fact (and yes, that is as scary to type as it is to consider in practice).

But a map is always better than the other option: the vacuum.

Taking the same sign vandalism, the vacuum rhetorician tells you the story and says, "That was wrong, the people who did it are bad, and I will never trust them again." And that's it; they've built a solid wall of certainty you can't see through to their reasoning.

These are not logical structures, they are the results of submerged processes that could hinge on all forms of fallacy or irrationality or even deep bias. But who knows, because this is the rhetorical equivalent of a kid responding to a math problem without showing his work. Right or wrong, you have no idea how that kid ended up where he did.

That's the vacuum. In terms of a math problem, it's confusing and counterproductive. In terms of the sign vandalism, it's problematic.

In terms of where we are in America today, it's terrifying.

Post-Election Conversations…

Photo Credit: presbylutheranism.com

A follow up on yesterday’s post. You can find it here.

I went to bed last night knowing that my son’s fears had been realized in the election, and also that he didn’t know yet. I found him sleeping in our room again because of his agitation.

I didn’t sleep well, and then my alarm went off. He wasn’t even fully awake when he asked:

“Who won, Dad?”

A note before pushing on: this isn’t likely to go where you think it will.

I answered honestly and held him as he tried to figure out—out loud—what it means now that what he was afraid of is real. I did the same with all three of my kids. It was a tough morning.

Here’s what we have decided so far. This election is over, but its challenge is not. What has been exposed by the process is ugly, but ugly has always been with us. And there is no option of checking out as if we bear no role in responding to what we see.

So we will:

choose hope over despair;

look for those who are hurting or afraid and respond with love;

listen to what to the words and stories of those who are usually silenced;

speak truth into the vacuum of bias and division we live in;

refuse to limit who we are because of who others want us to be;

and refuse to allow injustice to pass in silence.

If there is a mandate in this election, it’s that this country needs to find its heart. If we do, we need to use it rather than guard it. Ours is the sin of believing the world can only be only right when it resembles our version of how it should be. The suffering that myopia causes and has caused is enormous.

I’m looking to atone out loud for the sake of my kids and my country.

Post Script: Two incidents of note happened after I finished writing this that I think speak to what I’m working on here.

First, when dropping my sons off at school this morning, my parting words were, “Choose hope and look for people who need help.” As they walked away, another parent pulled into the loading zone and as his kid got out I heard, “You tell people how wrong they were and how Donald Trump made those idiots see.” They both laughed.

And second, I’ve already heard from six students trying to figure out how to understand their world in light of this paradigm shift. All have been openly harassed this election season for the color of their skin or their sexual orientation.

If you have said, “Make America Great Again” at any point, start by fixing these.

An Election's Eve Note...

I shouldn’t be writing this. I have other things to do. And yet…

…last night I walked into my bedroom to go to sleep and found my son curled up on the floor next to our bed. On our covers, he’d left a note.

“Please don’t move me….I’m worried about what will happen tomorrow.”

That’s not the whole thing. You don’t need the rest of his fears about today’s election.

You need to think about the role you’ve played in them.

My boy is nine and deeply empathetic. He gets it from his mother. His antennae are more sensitive than most, his words incapable of capturing yet what he’s picking up. But he’s catching our transmissions. And he’s drowning in what we all know about these politics as unusual.

We’re not ok. We should be worried. And we should be better.

The characters we should be impugning are our own. The values we should most fear have been on full display. And the fear in my son’s note is right now our legacy.

I’m old enough to know our country will move on after the votes are counted and that the terrifying shit show we need to address as a culture began well before the clowns took over this particular rodeo.

But what I think my son in most scared of is the conclusion I’ve come to at the end this long national failure of character.

We lack empathy. All of us. We can’t see each other.

How many think pieces on racism, classism, sexism, partisan-ism, and dogma do we need to see we’re growing increasingly blinding to who we’ve become?

How many polls results do we need to see the grand canyons we’ve so willing dug between ourselves?

I wish I felt more hopeful today, had some semblance of civic pride. History will be made one way or the other. But no candidate can step into the void we’ve created inside ourselves. No law will begin the hard, generations-long work needed to draw us together in ways we’ve only ever experienced in faulty rhetoric and nostalgia.

And no amount of worry on our part will fix this either. Worry is why we’re here in the first place. Worry about ourselves, our needs, our wants, our place. We won’t share because we’re convinced only we can see the world and what it needs clearly.

Clearly, we cannot.

Consider my son as I have: one small canary in a coal mine we should have abandoned long ago.

Go ahead and vote your conscience. But make sure you’ve found it first.

My interview with Ryan Gattis via the 1888 Center podcast, The How The Why

New Today: The 1888 Center's podcast, The How The Why, has posted my spring interview with Ryan Gattis regarding his novel All Involved. In it, we talk creativity, L.A. fiction, community, and maybe the Donut Man. Give it a listen here.

writing difficulties...

An observation:

Writers make difficulty by design. At least, the ones who make the most sense to me.

An explanation:

Writers, it seems, must find complications in life in places they could, ultimately, ignore if they weren’t cultivating a sense of struggle. Some might call this a pose, an air, a mantle tossed over their shoulders to approximate weight they don’t always actually carry. To be sure, writing is to accept a very privileged position in culture: an intersection of time, affluence, attention, and the assumption people need and want the results of those three things. Toward that end, they complicate living.

A (personal) metaphor:

This posture is faintly akin—metaphorically, of course—to the act of cutting, though not as externally damaging. Life is not controllable, and those things I actually cannot control are much scarier than the affectations that accumulate in my collection of what makes me “difficult.” Small phrases like incisions applied with precise control dissipate my unimpeachable sense of being unable to stop the world’s spin when chaos threatens to swallow me.

An amplification:

The world screams for our attention, to grab us by the ears and eyes and skin and impose itself. It seethes through broken teeth curses in broken children sold to satiate its anger; in hate masked as “common sense” and “heritage;” in losses made invisible by the uniquely human desire to turn away in order to protect our comfort.

A diagnosis:

However, good writers—by nature and by nurture of difficulty—cannot turn away. They need not even see the whole picture in order to extrapolate out the worst of cases in the best of circumstances, but they keep looking anyway. It’s their gift, if one can call it that. More, it is their responsibility.

A prognosis:

The cost of that privilege is so often a writer’s self-imposed debt.

I write because maybe.

“Why write? As soon ask, why rivet? Because a number of personal accidents drifts us toward the occupation of riveter, which preexists, and, most importantly, the riveting gun exists, and we love it." —John Updike, "Why Write?"

Why a person writes is something they should consider and, ironically, write about. Every so often, we need to remind ourselves why we need to string our words and dreams into something more.

This is an exercise I have all my students take part in, and, I guess, something I haven't done in a while. You can see my last attempt here. So here's my current answer to the question we all need to answer: Why, with all the other options we have, write?

I write because I breathe. When I breathe, I exist. When I exist, I understand that others exist. And when I understand others exist, I want to know them.

Or, maybe, I write because I can't know them. Not in a way I want to. Not in a way that moves beyond limited interaction. Not in a way that makes them real.

Or, maybe, I write because real is so illusory. It shifts at the exact moment I reach out to grab it. At just the moment I see it clearly. At just the second I've chosen the right words.

Or, maybe, I write because it really isn't a choice. Words are compulsion. Words are affliction. Words are skin, once torn, growing slowly back together.

Or, maybe, I write because living is the wound and stories my salve. My bandages. My scabs before scars destined to be their own stories.

Or, maybe, I write because my scars are not enough. They are just my own. They are just my sins. They are just my fault.

Or, maybe, I write because my faults are not their faults, but their faults make me human when I hold them next to mine. They make me aware of my imperfections. Aware of their human character. Aware of the fact that our humanity is bound up in these.

Or, maybe, I write because humanity is lost on humans until we arrest it in the amber of words. Grab it with the swipes of my pen, the strike of my fingers against the keys, the frozen flat surface of the printed page that captures my heart in ink.

Or, maybe, I write because that capture is the only real metaphor for freedom we have. Illogic as sense. Impossible as practical. Walls as open windows.

Or, maybe, I write on the very walls I want nothing more than to transcend. Maybe those words are my climb. My scale. My ascent.

Or, maybe, I write because there is nothing left to ascend save the holy moment of knowing my unknowing at the moment it ceases to lead only to the unknown. Doubt transubstantiated. Fear crucified. Hope resurrected.

Or, maybe, I write for precisely that maybe. That open question. That expansive possibility. That known unknown.

I write because maybe. Maybe.

until we are all free...

A note on this post: the content of my thoughts in this post comes in response to the wisdom of the people of color in my life (a group that includes people I’ve never met, but whose work in writing their experiences and perspectives has broadened my notion of everything). Nothing I’m saying here hasn’t been expressed by others. I am indebted to their contributions, as I would not see the water we swim in as clearly without their help. This is merely a space for me distill some of my own thoughts on the matter. I hope they challenge you as they do me.

As a parent, some of my most difficult conversations revolve around trying to help my daughter find her place in this world. Case in point: our recent discussion about how the Constitution was not written with her in mind at all.

My daughter is a young black woman, which is a precarious position in our society. As she becomes more aware of the history of her adopted country, she has to come to terms with something I never will. At the inception of America, in its most prized and lauded documents, she was invisible.

Because she is black, she was not afforded full personhood. Because she is a woman, she was even further erased. This is the reality of our nation’s origin story.

Unfortunately, that reality is not merely an artifact of the past. In many ways, my daughter, radiant as she is, must still fight to be visible like most women of color. And that fight, as she is learning from the cycle of violence that plays in our nation on repeat, is not merely rhetorical.

To live in America is to live in a tension between the idealized and never achieving that ideal. It always has been. For some, that tension is intellectual, a form of disappointment that things aren’t “the way they should be.” For others, however, the cost of being caught between the dream of American possibility and the reality of its brokenness is violence, fear, and, in too many cases, death. This, as much as anything else, marks what we now commonly describe as privilege.

The divide between these two cultural experiences is that we live with a nostalgia for something that never existed, a type of historical storytelling that has often been a form of violence employed for the sake of preserving one group’s sense of itself at the expense of—and often through the complete erasure of—another group: their identity, their agency, and their lives.

Do you ever wonder why a criminal of color is so easily cast as representative of his entire racial or ethnic or religious category while a white man who commits the same crime is solely responsible for his actions? Do you ever wonder why you never wonder that? Again, this is what people mean when they ask you to check your privilege.

An example: the political slogan “Make America Great Again.” To adhere to this notion, that there is a historically better America to return to if we just try hard enough, is not new. The current candidate slapping the phrase on ugly hats did not originate the idea.

It’s always been with us; the elusive sense that returning to a simpler time would soothe today’s troubles, would save us. It’s why so many movies in the 80’s sought solace in taking us back to the 50’s.

But this is only a solution if your proximity to the Great American Tension allows you to see that earlier time as safe. As my pastor, a black man, put it, “What part of the past do I want to go back to? When was it better here for me?”

Again, if this perspective has never occurred to you, yours is merely an intellectual tension. If you don’t look at our history and recoil at the very real danger of the internment camp, the lynching tree, or the reservation, you long for a time that only more fully and openly privileged a very small group of people: a group you may not have been a part of even as you imagine yourself being so.

This is my problem with people who default to the unflinching rhetoric of valorizing without any criticality the work of the American Founders. Yes, they wrote documents laden with immense potential to liberate humans and create space for equality that has never really existed.

And yet, they lived lives that directly undercut the potential of their words and blocked the path to the very equality they championed for so many people in this country. In essence, they proved that even implements designed to heal and empower become weapons when they are applied selectively to benefit only those we most resemble.

And to create these benefits, we have kept them from others time and time again, right down to our three most cherished freedoms: the pursuit of happiness, liberty, and, in far too many violent instances, life itself.

This is why “I can’t breathe” are not merely a man’s dying words. This is why we should not fall victim to the pandering sentiment of “Make America Great Again.” And this is why we should never say #AllLivesMatter, because we don’t live that way enough yet to claim it as our aspiration.

Instead of nostalgia, which has literally killed people, we need hard reality, honesty that does not flinch or recast the world in ways that make us feel better about ourselves, justice that is not selectively employed, mercy for those who are begging for us to acknowledge their suffering, and an actual attempt to hear each other in the midst of pain that renders us deaf.

I actually believe in the potential of the principles our country was founded on. If applied to everyone in equal measure, this would truly be the great place we imagine it to be.

But that’s not our reality and will not be until we do what neither the Founders, nor any generation since, could: value equally the humanity of everyone and admit that we are part of the blindness keeping us from doing so. This is the American greatness I want my daughter to experience.

Word G(r)ift

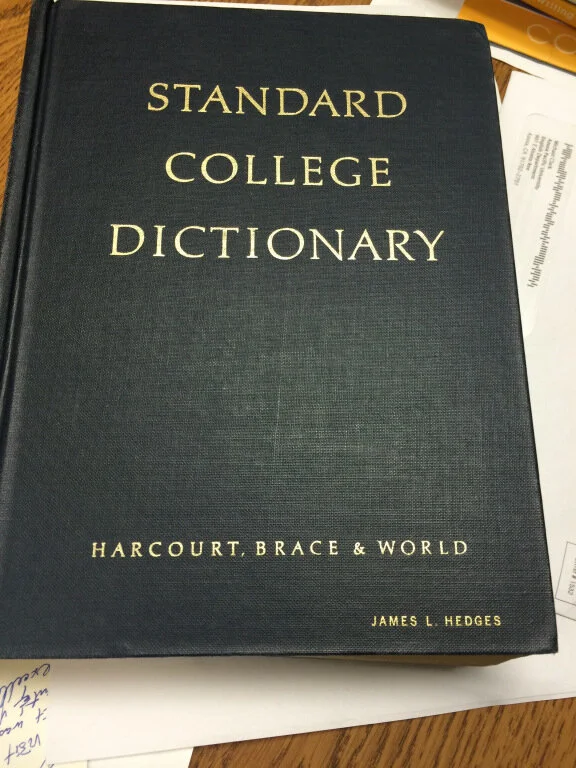

I had to drop some books off in my office* the other day, an occupational hazard of the job. Books find me, I swear, I don’t go looking.**

I had no intention of staying in my office any longer than necessary because that’s how work you weren’t planning on doing attaches itself to you. But as I turned to go, I noticed an older looking book I didn’t recognize sitting in the center of my desk.***

Upon closer inspection, the cover read Standard College Dictionary with the name “James Hedges” pressed into the lower right hand corner. This was odd. Dr. Hedges was the chair of the English department I now teach in when I was an undergrad, but he retired well before I was hired back as a professor.****

Side note: The at that point unknown gift giver had no way of realizing how appropriate his gift was. When I was six, I went on vacation with three books: an Archie comics collection, The Black Stallion, and Webster’s English Dictionary. I read every word in that dictionary before we got home. My family still finds that funny.

Flipping the book open, I found a letter tucked inside. In short, another former professor and now retiring colleague from the Communication Department, Dr. Ray McCormick, was leaving me the dictionary as Dr. Hedges had given it to him when he retired.

The note is simple and, in McCormick fashion, devoid of unnecessary emotion. As my rhetoric instructor, he emphasized that while form is message, our message must be true and useful. These were our guidelines. And yet…I can’t help being moved by his last line.

“On your retirement, pass it along to the next guy!”

There’s a certain sense of validation in the assumption that I’ll make it to retirement in this field. On the surface, it’s a small note to be sure. But Ray knows me; the confidence written into that line matters to me, as do the other votes of confidence I have received from time to time from former professors-turned-peers.*****

They remind me to look for ways I can call out talent and potential in my students. One day, I’ll likely be handing one of them that old dictionary with my own note in it.

Notes:

* I still find it immeasurably weird that I have a job that provides me an office to go to, which makes the gift I found on my desk even more touching.

** That is a categorical lie. I’m always stopping myself from buying books.

*** Which did not automatically mean I had not put said book there, merely that I could not remember doing so. As it turned out this time, though, I had not.

**** This turn of events monumentally more surprising than the whole having an office deal.

***** One of the gifts and oddities of working at the school you graduated from…

Things undone

Discoveries like this one have a way of moving me in two directions at once: back in time and deeper in the present moment. This truck makes me think of what I've never finished and, if I'm honest, what I might never.

When I was a freshman in college, my dad found a 1946 Ford pickup much like the one in this picture. I noticed this one on my morning walk, a practice that has inclined me toward my age in ways I had yet to discover. I walk in the five o'clock hour of the morning as the sun comes up with the acid in my stomach for most of the first couple miles because I hate early mornings. But I hate how sedentary I have become more. So I walk.

There are many benefits to this choice I've made to get moving before most of the LA traffic and people in the sleepy suburb we live in (I tell myself). I'm done before my kids get up for school. I'm guaranteed to accomplish something with my day (a feeling writing has not provided me for a long time). And I am awake enough to have lucid conversations with my family before the weight of my daily schedule renders me monosyllabic. And most important, the walks force me to slow down and contemplate what I would otherwise push right past toward the goal of completing a regular workout.

Who's got next? Pretty sure it's Amish rules on this court.

Like that truck, I end up finding small pieces of the neighborhood that make me smile pretty regularly. For example, this random basketball hoop hanging from a telephone pole in the neighborhood. Not sure who's hooping next to the faux-farmhouse these days, but the former player in me appreciates the nod to the game I love.

Sunrise over Uptown.

I also get to see the sun come up over the foothills, a form of compensation I have not earned much in my life. And there are moments, like this one, where I forget for a second that, in the past, I only ever saw skies like this at the end of long, sleepless nights.

But back to the truck from the beginning of this post. So my dad found this truck, out in the country outside of Modesto, California where my folks had recently moved, and he bought it as a project. It needed work—body, frame, engine—that he intended to share with me over the next couple of years. We'd talked project cars for years, but we never had the money or the time for one.

So we started when I finished that first year, tearing the truck down to the frame and pulling the huge engine the previous owner had dropped in the thing and then grinding and sanding and working over the body panels between the demands of Dad's job pastoring a new church and my 15-17 hours a day stocking shelves for Pepsi. I think I worked on the hood alone for more than a week.

As we worked, Dad told me about what he wanted to do with the truck. Pull the original bench in the cab and replace it with bucket seats. Pull the rusted-out bed off the back and replace it with a flatbed of treated oak panels. Beef up the rear axle with a heavier gauge of gears to handle an engine and transmission combo that was much larger than Henry Ford ever intended for this model.

He also told me stories of the cars he'd worked when he was younger while we poured over catalogs and went to stores and junk yards looking for parts we needed at prices my folks could afford. And, more than anything, we dreamed about what we hoped our truck would turn out like. We scraped and ground and worked until, as they all do, that summer came to an end and I left for Los Angeles and my sophomore year.

And that was the end of it. I never lived in their house again, my summers committed to jobs that would help pay for my next year of school and internships I hoped would get me a career after I was done. I'd check in every once in a while about the progress Dad had made, but it slowed and then stopped and then he'd sold the truck.

I still remember standing in the space it had occupied in the garage the first time I visited after he sold it. It felt like a personal failure. Like I'd lost the chance to help Dad do something he'd always wanted to do. My parents were the types who sacrificed a lot to raise us, and I just wanted to give a little back. But life doesn't always give that kind of time to what we want.

Years passed and, other than in the scattered conversations we had about that truck, I hadn't really thought about it until I came across this one on my walk. It's not the same (a double axle vs. our single, original engine vs. the Pontiac beast we had, it's likely a year or two more recent a model). But for all intents and purposes, it is the same truck and I felt that same feeling of loss...but only for a moment.

Call it part of the aging process, but I've learned that some projects—some seasons in life for that matter—are brief and never meant to be complete. Rather, they highlight our desires and, if we're fortunate, give us even a moments' time to engage in them. For a few months, my dad and I shared a project and a dream for what it might become. We never finished, but we'd made a point of working together simply because we both wanted to. If there is a more relevant model of being a father, I haven't found it.

I guess what it reminds me is that not everything I do needs to be completed to be of value. It's the willingness to engage the passion and need of my moment that matters most. This, when I allow it to be, has acted as leavening to my Type A tendencies.

I took a picture of the new truck not to write about it, but to send it to Pops. His reply: How much is the guy asking? It wasn't for sale. But then, three weeks later, it was. So I'm inquiring, reminded that just because a dream doesn't happen on our schedule doesn't mean it won't ever be realized.

41 for 41: The One-Shot Version

Author's Note: In the fall, I published the following essay a piece at a time, a series of reflections on living 40 years in this place and in this body. For my 41st birthday, I'm publishing it again in its long form entirety for anyone who wanted to see the piece in its unified version. Thanks in advance for reading if you choose to do so. Also, if the length of it already has you tl;dr'ing it, you can still find the component parts in bite-sized entries just below this version.

-Michael

41 FOR 40

For most of my childhood, I expected to be dead by 30. I had no compelling reason to believe this. My health was excellent. There were no hereditary conditions driving my fear. But it was real and present and I fully expected to die young.

Maybe it was the Cold War ethos of the 80s; the thought that the bomb was just a day away from dropping. Maybe it was the end of days talk that still runs through churches periodically and seems to coincide with my general notion of how insignificant I am. Maybe I’m just a fatalist.

Then I hit my 30s and I was left wondering what happened and what I’d let happen as a result of fearing I’d never make it that far. Anyone who knows me knows I don’t sleep. Haven’t for a long time. I guess there could be a connection. Then again, correlation does not automatically signify causation, or so my grad school friends are fond of saying.

So, now I’m a year past 40 and I decided I needed to take some stock in that. A decade older than I thought I’d ever be. Middle aged and everything. Three kid having and everything. Gray hair finding and everything. Formerly minivan driving and everything. Get-off-my-lawn-yelling and everything.

The results are the following 41 ideas that are not lessons for others, merely vistas I’ve stumbled upon along the way. They were written individually over a six month period. Interestingly, when I looked at them as a whole, I seemed to be speaking to myself in groups of two. Most are short and some a bit longer. But all gesture at the core of who I am.

Look, I figure turning 40 allows me to invoke honey badger privilege with this one. I do what I want. What follows, then, is the essay in its entirety rather than the component parts originally spread out over a month of posts. I hope you’ll give it a read and, if you feel so inclined, let me know what you think. I’m open to conversation on any and all of these thoughts.

Love and Grace (If You Will)

Love done right is exhausting. If you aren't moved from the center of the frame by how and whom you love, you aren't doing it right. If you aren't challenged and discomforted by how and whom you love, you're not doing it right. If you love only because you get something out of it, you're not doing it right. If you love only the people and things you’ve deemed deserving of your love, you're not doing it right. If the way you love doesn't cost you anything, and possibly everything, you're not doing it right.

***

Grace is the most difficult and most necessary choice we make, and we don't make that choice nearly enough. The capacity for grace in humans is evidence of the divine. The lack of grace in humans is evidence of our need for that divinity. I am increasingly convinced that grace—dirty, costly, unrequited grace—is more important than love because love can't be real without it.

And let's be very clear: grace is not ours to give. The moment we begin thinking of it as our gift to others is the same moment we’ve made it about ourselves. When we see grace as something we have to give, we see ourselves as superior to those we are seeking to give grace. This echoes the notion of tolerance, which inherently establishes one group as tolerant and another as tolerated. Most people I know hate feeling merely tolerated. In the same way, most people hate it when those who claim to be helping them are really helping themselves.

Grace, rather, must be a lifestyle, something people cannot separate from who you are. It's not a pose or a tool in the toolbox of being a good person. It is the toolbox.

Mirror Weakness

Myers and Briggs are liars. Strengths Questing inspires a form of tilting in which the windmills exist, but the knight—errant or otherwise—does not. You are not any of the cast members of Friends, no matter what BuzzFeed tells you. Personality inventories offer concrete notions of the self to those who take them too seriously that are as much fiction as any character invented by any writer ever. I’m not implying these “tests” are irrelevant or do not reflect certain character traits we often possess. Rather, it’s what we do with the results that’s dishonest; lies coming in the form of turning very faint glimmers of the complexities comprising who we are into stable, quantifiable badges we wear at corporate mixers or excuses we use not to push into our weaknesses when that’s exactly all we need to do.

***

On pressing into weakness:

I’m going to be a little lot vulnerable here. I have devoted most of my adult life to writing. And 22 years on, I can say one thing with certainty. I don’t know if I’m any good at it, and my suspicion is that I may never be more than passable.

This isn’t a case of compliment fishing. I’m not asking for people to tell me I am. Please note the lack of question marks.

Rather, I’m being as honest as I know how to be. Writing is an uncertain enterprise. I am never certain I’ll have an idea when I sit down to the keys. I am never certain the ideas I do have are worth writing. I am never certain I’ll be able to write in in such a way that does my ideas justice. I am never certain anyone else will see my stories and ideas as worth publishing, and my stack of rejections doesn’t necessarily help with that. But most of all, I am never certain what I write will matter to anyone else.

Add all that up and the fact that I don’t know if my writing is any good or not is really the most lucid conclusion I can draw.

And still I write. Maybe it’s stubbornness. Maybe it’s pride. Maybe it’s a distinct lack of creativity in that I don’t see any other options. I guess maybe I’m just too curious. About the next corner. The next idea. The next reader. Maybe it’s that I just haven’t reached the end of hope yet. So I write.

Student at the Podium

Teaching has instilled in me many lessons. One of my favorites is highly counterintuitive. I want my students to surpass me in their work and thinking (which, in my case, is not that big an ask). What’s interesting is that wanting them to be better than me makes me push more diligently to improve my own work. It’s not competitive instinct. Neither is it a professional jealousy. Rather—and it has taken me a long time to see this—it is my way of honoring their effort. I’d rather my students see me as the writer working right alongside them than that guy who got published and talks about it.

***

In the same way doctors make awful patients, teachers, it would seem, make deficient students. At least that’s been the case with me. I suspect the act of working to make sense for others disables the ability to do so in me at times.

For example, here’s a life lesson only recently learned. I hate clichés. I try not to write with them or, more importantly, live them out. At the same time, I teach my students not to fear clichés in the early stages of their writing. Clichés, I tell them, are merely easily accessible expressions for the deeper sentiments their scene or sentence demands—a depth that is just not consistently reachable without completely destroying any storytelling rhythm one has achieved while still trying to figure out what they want to say in general. Clichés are only harmful if you don’t go back and make them better, more expressive, less expected by the audience once you can see the larger picture. If they remain in your final draft, well, that’s just lazy.

Back to that life lesson. The fear of living clichés is the most insidious cliché of all. The thing is, clichés can only be seen in reflection, not while we’re in the process of living. Trying to avoid them as you go is paralyzing and actively makes cliché your experiences in the process. For more on this, see hipster culture.

Rather than avoiding them, we should choose to live more and more consistently reflective lives. Then, like any good writer, we can avoid lazy storytelling by revising for originality before moving forward with living better, more expressive, less expected lives.

No Such Thing as Political Love

Your political leanings are not right. More often than not they should be left out of the work that needs to be done. There is nothing progressive about loving others. Nothing is accomplished when we are conservative with our engagement of the worst elements of our humanity. If anything, the way we politicize our views of the world keeps us from listening, loving, and being graceful when that's all we can and should do. Seriously, try to wear yourself out in doing what is most helpful for the least of us rather than arguing about things that only matter to those who have the most. I’ve read this sentiment somewhere. The font color was red I think…

***

Increasingly, I grow tired of the words advocate and ally. I understand the intent and feel better about them than the alternatives. But the results are the same. We plug our efforts into a cause and that cause into the same binary perception of a war have been told we are fighting, whether that fight be cultural or religious or personal (though putting or in the last phrase feels completely artificial). We exist, so it would seem, in shifting states of us and them where winners or losers are judged to be on the right or wrong side of history and what matters most is winning.

The problem—and we all really know this deep inside—is that the game is never fair and the way it is rigged so often means winning is still losing when we embrace a larger perspective. I would argue this notion of living guarantees no one ever wins or loses because, shockingly, life is not a game of horseshoes (a game of horseshoes!).

Instead, we should stop playing and take reconciliation seriously. It’s our only hope. Sure, it’s messier and more difficult. For reconciliation to work, everyone bears fault and blame and responsibility, though not, to be sure, in equal measures. And most of all, everyone must be honest. Unvarnished even. To be reconciled is to expose our rough and wounding edges to ourselves as much as we do to each other, letting their proximity and our steadfast, repeated recommitment to love each other like we love ourselves sand those pieces of us down until we fit together as equally valued, equally seen souls.

Family Extends

On my patriotic leanings: I'd rather live in a country that bankrupts itself to help people who cannot meet their own needs than one that grows rich on the backs of those very same people. I'd rather live in a country that seeks justice than one that is only concerned with what it deserves. I'd rather have less so that others have enough than have more and cause others to go without.

***

On racism: I taught a humanities course that focused on race in America several years ago in Milwaukee, a place that has been referred to as the second most segregated city in the United States. About halfway through the term, in the middle of a discussion of the writing of James Baldwin, one of my students leaned back in her chair and sighed.

You know, racism is only a problem because we keep bringing it up, she said. If we’d just stop talking about it, we’d see it’s not a problem anymore.

The girl next to her shook her head. I used to think that way until my dad told me about what he goes through being black, she said. I guess I just haven’t seen it as much because my mom’s white and people don’t assume I’m black too.

The first girl stared at her for a full minute after the conversation moved on, replaying everything she’d said about race that semester, if I had to guess what she was doing. I can’t recall her saying anything else aloud for the rest of the term. Her retreat into silence still grieves me.

On a related note, I was recently told, anonymously, by a student in my world literature class that I need to “stop white shaming” my students. Weird given that I am, in fact, white.

Make of those two stories what you will.

***

People ask me about adoption pretty regularly. Sometimes they want to hear my family’s story. Sometimes they want to talk about being a transracial family, though they rarely possess the term transracial to describe us. Sometimes they want to ask questions about blackness they wouldn’t think to ask a black person. Sometimes they want to ask questions about adoption they shouldn’t say outside their heads. Sometimes they want to ask if I think other people should adopt, which is so often code for asking whether of not they should. Sometimes they want to pin a medal on my chest I didn’t ask for and don’t think I deserve. Sometimes they want to accuse me of some kind of racially or nationally or religiously or socioeconomically privileged agenda in our choice to adopt. Sometimes they want me to speak for adoptive families I am not a part of. Sometimes they want me to make our adoption a bumper sticker of affirmation.

They never ask me those questions about my biological children. I hope it occurs to them that my daughter realizes this, even as I’m pretty sure it does not.

(This) White Man’s Burden

I still maintain hope that, one day, we can accomplish Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream of judging people by the content of their character and not the color of their skin. A caveat: this would not negate our ability to see color, merely integrate the notion that in our differences we are still all of the same worth, something our culture is still too broken at this point to do. This has been my hope since I first heard those words as a child. But now, I understand that Martin was speaking about the character of white people.

***

My mom took me to task once for wanting the world to be fair. We were driving, the two of us, in the middle of nowhere across the high desert on the way to my aunt and uncle’s place in the mountains. It may or may not have been the trip when she let me drive the car, illegally, to get some practice behind the wheel.

I thought, at the time, she was critiquing a complaint I was in the middle of making about something I should have been allowed to do as the 14-year-old master and commander of my own destiny. That misunderstanding later evolved into another as I reinterpreted her words to mean the unfairness I called out would never change. That unfair is just the way things are immutably.

I think I see it now. What my mother was trying to get me to understand is that merely diagnosing something as unfair is never enough. If we aren’t working to make those diagnoses cures, well, we’re merely part of the unfairness. And some of that work must be identifying how we’ve been part of that unfairness from the start.

Otherwise, we cannot uphold the vow to first do no harm.

My Fanhood

I still love sports. Few elements of American culture have the ability to call out the best in us the way the games we play do. Or highlight the worst in us. Our commitment to each other and our utter greed. Our shared sense that life should be fair and our continual pursuit of ways to game the system in our favor. Our desire to push the human body beyond perceived limitations and our willing blindness to the fact that the pursuit so often ends in a sacrifice on the alter of performance offered in the most unhealthy ways.

Where else but in sports are the ills of our culture—racism, sexism, poverty, usury, hubris, violence, and more—so clearly seen and celebrated? Where else can the best parts of us—heroism, honor, charity, fairness, competition, belief, teamwork, and more—break through and subdue, if even for a few moments, the ills I listed just a moment ago?

Please don’t read this as some sly, ironic takedown of sports. I meant the words I started this passage with. But love is never simple. And loving something means never blinding ourselves to its entirety. That would be lying, not love.

***

On arguments regarding historical greatness:

Michael Jordan is not the greatest player in NBA history. Neither is LeBron James. Or Kobe Bryant. Or Wilt Chamberlain. Or Kareem Abdul Jabbar. None of them run out of hands for their championship rings. None of them owned a decade in its entirety. None of them were coaching their teams while winning championships. None of them give as much credit to their teammates as he does. And I’m a Lakers fan; so saying this hurts me deeply. But it’s Bill Russell. Eleven rings don’t lie.

Like I said, love is never simple, even regarding sports.

Everybody Hurts…Sometimes

Little injuries from years ago have an accumulating impact on my body today. When I played sports, I played through them. Ignored them. Refused to admit I had them. Now, I am a product of them. And when I move and feel their legacy in my joints and bones, I also feel the need to repent for the injuries I may have caused others in my clumsy path from birth to today. To make amends for them, at least in some small way. If you think I'm still talking about physical injuries, you're not old enough yet.

***

I remember, when I was growing up, listening to more seasoned people talking about how their old knee injuries allowed them to predict shifts in the weather. Now I’m them and my old knee injury only allows me to predict how much less I’ll be able to run in five years. I’m not sure if that means they were overstating their psychic arthritic joint abilities of premonition or I am merely incapable of reading the signals mine are sending me over the noise and distraction of my life. Whichever it is, I’m just as bitter about not having that superpower as I am at not having a hover board or self-lacing Nikes.

The Topic of Cancer

Cancer is an indiscriminate bastard. It takes so many and passes by others whether or not we've painted our door frames with medicinal and spiritual blood. Young and old, fit and fat, cancer with its hundred heads doesn't have a type or target. It settled in my grandfather's brain. It revisits my father's skin regularly as if testing for weaknesses in his defenses. My mother beat it back twice and almost lost her voice doing it. It began unobtrusively behind the knee of my first choir director and advanced until he could retreat no more. My list could go on, as I’m sure yours could as well.

The day after I wrote this passage just a few months ago, I woke to the following two pieces of cancer news. An old friend was celebrating the six-month mark after his leukemia-necessitated bone marrow transplant. At the same time, I awoke to find waiting the obituary for the sportscaster I most identify with my youth. Stuart Scott was only nine years older than me and the worst word in this sentence is was. I am aware that was will apply to us all eventually, but cancer seems bent on robbing so many of their is and will be.

***

As I said at the beginning of this series, I didn't think I'd live to see forty. Most of the time, I'm glad I did. All of the time, I am mindful of those who didn't for whatever reason. It also makes me wonder how we can care more about the losses around us than we do right now, particularly the ones that seem so unfair. It makes me wonder if the four-year-old girl I saw in my daughter's home country making gravel by hand has become one of those losses. It makes me wonder if the guy I grew up with who was in jail at 12 for selling drugs made it to adulthood. It makes me painfully aware that many of the people I’ll wonder about next are already gone.

Do I Not Amuse You?

I am funny and I feel guilty for it. I have no idea what to do with that disconnect within myself. That could be why most of what I write tends to be serious. Or, maybe I'm not as funny as I think. It's probably that.

***

People who know me personally and read my work often find the two discordant. They wonder why there is not as much humor in my stories on paper as there is in the ones I tell. One reader, after finishing a piece I wrote, told me I “traffic in tragedy.”

That’s funny. I prefer to say tragedy, so often, traffics in us.

In the Hollow of the Quiet

This may be a bit lot more vulnerable than my passage about whether or not I’m any good at writing. At least there’s some uncertainty there. My struggle with depression is, on the other hand, much more certain than I’d like it to be. It’s there, the same way that in the middle of the day when the sun is at its brightest, the nighttime darkness is merely a half revolution of the planet away. In the middle of any emotion—the happiest happiness, most joyous joy, most contented contentedness—it is just as possible that I will crash as when I am weary or sad or “most likely” to “get” depressed.

That depression is not about its circumstances has been the most difficult lesson to internalize. I feel so guilty about my bouts with it. I mean, what do I have “to be depressed about?” I have the best partner I can imagine in my wife. I have three legitimately fantastic children. I have a family who loves me and who I love. I have in-laws I feel the same way about. I have friends. I have a fantastic job. In short, I have all the things that should stave off depression.

Taken a step further, I have my faith. It is the ultimate hope I cling to, in the face of all of it. But within my community of the faithful, the prevailing logic is that should be enough. That when I am depressed, I suffer from a lack. I am not being thankful enough. Not grateful enough. Not humble enough. Not faithful enough.

I’ll be the first to admit that I have thought all of these things about myself. More honestly, in the middle of my darkest, heaviest, most disconsolate places, I’ve lodged these accusations against myself, drawing an easy conviction in the court of my heart.

Before I become too easy a caricature, yes, I am aware depression is a mass of chemical, neurological, biological, seasonal, circumstantial, and inter/intrapersonal complexities. It’s not always only a matter of praying the gray away.

That’s what makes it so difficult. If, as I posit later, that doubt is the crux of faith, then I find myself at an uneasy crossroads because it would also seem to be the crux of depression. I wish I had an answer to why those two seem to intersect so seamlessly. Probably because grace requires empathy for the entirety of the human experience and we are so infrequently able to see that.

***

On silence:

I have a slight case of tinnitus, likely the product of flouting headphone volume warnings as a kid.

I live in the Los Angeles area. There are so many noises around me I don’t even register consciously that I’m fairly certain we all suffer a form of deafness doctors just haven’t given a consistent label yet.

My favorite place in the world is on the shore of the Pacific Ocean, in a place called Cardiff by the Sea, California. I like it best when the tide is out and the fog is in. I think of these conditions as a more real form of silence.

A few years ago, I hiked to the top of the tallest mountain in the lower 48 states. When I reached the summit, there were at least thirty other people up there. They would not shut up.

I like my wife a lot. She’s my best friend. When she’s not talking to me, I find myself filling the quiet gaps, trying to goad words out of her. I despise the thought that one day I won’t get to hear her anymore.

Silence is not golden. Understanding why sound matters because of it is.

Successful Failure

We are the product of our failures much more than our successes. Success breeds self-assurance that ends in repetition. Failure breeds self-awareness that ends in recreation. Only one of these is growth.

That sounds like a bumper sticker or, for the kids in the audience, a meme. So let's mess that up a bit. If you reflect only on what you've done well, you kinda suck. That nostalgia for your own history blinds you to the ways you need to be better. It keeps you from realizing that the measures of success aren't at all what you're holding onto.

Now, I'm not advocating a pathological fixation on all the ways we don’t get it right. For more on this, refer to my note on grace and realize that the same dirty, costly grace we need to show others can and should also be shown ourselves. It already has been. But this is reality: failures are who we are. Successes are the blessings we were fortunate enough to be standing next to when they happened.

***

I firmly believe that we are as much or more the result of what I call intrapersonal barriers as we are our willful constructions of who we want to be. Put another way, we perceive these barriers as the shadows we must grow out of to be seen as individuals by the world around us.

These shadows are so often the chimeras (no disrespect to Baudelaire) we carry through adolescence and into the rest of our lives; a powerful force in the shaping of who we are as a person, both in our own estimation and that of the people around us. To be sure, we make many defining choices. But it’s at least as important to note the choices we didn’t make that set up so many of those we had to.

Here are my three most prominent, in no particular order:

Growing up in a place where I was not a local and could never afford to appear to be.

Primary example: We were never poor, but we didn’t have all that much. In junior high, I transferred to a private school on scholarship. In the summer, my dad and I painted the bathrooms to hold onto that financial aid. Many of my classmates went on resort vacations or stayed in their “other houses.” In this case, it’s not about equating what I didn’t have with what people in poverty don’t. It’s about how comparing myself to everyone else established my “normal” for a long time.

2. Being the son of a pastor with no designs on being one myself.

Primary example: While trying out some adult phrasing in third grade, I told my friend Jason to shut his damned mouth. My first grade teacher overheard me and, with literal hands on equally literal cheeks, said, “Michael Clark! What would your pastor father say if he heard you say that?” Repeat that scenario for the next fifteen years.

3. Playing basketball in the same place as my brother (a MUCH better player).

Primary example: A referee stopped me during one of my first varsity games as a freshman. “Clark? Are you related to Paul Clark?” “Yeah, he’s my brother.” “Huh. I expected you’d be better.” For the record, my brother is eight years older than me and had to keep me from quitting the sport I love most just before my senior year.

Running to Stand Still (is still my favorite U2 song)

When I was a teenager, I ran track as a break from playing basketball year-round. I loved the way races shut down the outside world. I ran sprints—100, 200, 4x100, and the 400 if my coach felt like watching me pass out—and the mere seconds from gun to done were as close to meditation as I got.

I remember once, as a young kid, getting scared while running as fast as I could on the elementary school playground. I stopped and looked around to make sure I hadn’t started a tornado because, in my head, it felt like I had. I wasn’t that fast, but the speed we create when we’re little makes the world feel slower in ways we are not prepared to handle.

My final competitive 200 meter race started well and ended very poorly. I was on pace to run my best time ever in my best event and maybe—maybe—beat a guy I’d been losing to for four years. Coming out of the turn, my hamstring twinged, then seized, and then tore. I fell flat on my face. The race ended, some teammates helped me off the track, and we went on to lose the overall league championship by two points. If I’d finished second, we’d have won by six. It still bothers me.

When I was in sixth grade, my brother goaded me into challenging my 43-year-old father to a foot race. We ran about 40 meters and Dad destroyed me. I only found out after the race that he had been a sprinter in college. Hindsight and all. Fun fact: I never ran the 100-meter dash faster than my father.

I coached high school track for a while. One of my favorite drills was to send the entire team on a four-mile run at the very beginning of the season. I mapped out the route and sent them on their way. Then I drove to the run’s midpoint, located near a Baskin Robbins ice cream store, bought a cone, and sat under a tree while they panted by. As they passed, I told them I wasn’t tired yet. I like to call that team bonding. You’re welcome, Cardinals.

When I run now, there’s no danger of the kind of temporal displacement I felt as a kid. I haven’t sprinted in years. If I ran the 200 now, it would have to be timed on a sundial. I still feel my hamstring, but now it’s joined by an arthritic ankle, reconstructed knee, repaired hernia, and general sense of being elderly. I’m pretty sure a kid who saw me running recently went out of his way to push the crosswalk call button for me out of altruistic concern for my wellbeing.

***

When I was 19, I woke up one morning in my dorm room with blood on my pillowcase and the acute inability to make sounds happen with my voice. I went to a specialist who sent a scope up my nose and down into my throat, grunted, sighed, pulled the scope out, and set it on the tray next to him.

“Well, you won’t be singing anymore.”

“For how long,” I asked, accustomed to taking brief breaks that let my instrument recover.

“Ever. At least in any consistent way. Sorry. You just have a poorly constructed system.”

Twenty-one years on and it still feels like getting punched in the throat to even type those words. Singing was part of my identity. I miss it every day.

What have I learned from it? That losing sucks. That I could have done everything possible to save my voice and still lost it. That I never gave singing the credit it deserved in terms of how much I needed it. That I got to do some great things because of my voice and feel, in many ways, cheated by what happened.

Mostly, I learned that I was called to do something else and that discovering who and what we are supposed to be isn’t always a rapturous experience.

Story: Essential Foils

Stories are more important than details. Meaning must be made, even if you happen to think that everything is meaningless. Fiction is as true as truth when it wrestles with that great, gaping maw of life’s randomness. I'm not advocating the search for a grand narrative behind all of this. If all we experience is connected, we're not equipped to find the thread that holds it all together, even as sure as I feel that there is an intent in this all. Rather, I believe everyone should see the world in the context of story. Not one they are a part of, but one they are authoring. If you see life as a story unfolding as you move through it, your passivity actually hurts the people around you. If you see yourself as having been given authorship in your tiny piece of the larger narrative, your actions matter whether or not you think they do. In the cosmic scale, we write our universe because as broad as our reach has become, we are still always and ever beholden to this present tense second.

***

Every single human should take a creative writing class. I’m not saying that everyone should be a writer (see my earlier passage regarding whether or not I think I should be one). But everyone should consider stories from the perspective of a maker rather than merely a listener or reader. It will definitely change the way they see the people around them. It will teach them about those people, and, in contrast and conjunction, themselves. It might even teach those willing to listen a little something about God.

Listen Up

Listening is exhausting. Seriously, nothing highlights our radical self-centeredness as a species quite as much how far we will go to avoid listening to what others have to say. We’ve built monuments, communities, and systems that destroy all manner of life simply to keep from hearing each other.

***

My younger son, almost four years old at the time, sat in church with me one Sunday rather than go to his class in the preschool. Halfway through the sermon, he looked up and said, loudly, "This story is taking too long!" I hope more than just our pastor hears Judah, because he nailed it.

Single Track Thinking

I am deeply disenchanted with almost any form of singular narrative. The more people claim a singular sense of anything humans live through, the less I can take what they have to say seriously. Racial experience. Political primacy. Educational success. Socioeconomic “reality.” Lived experience. Religious norms. Gender expectations. When any voice or collection of voices claims to hold “the” representation of these and other complex, dynamic, multi-faceted experiences, I’m out. We fear complexity and construct simplicity, inventing lies that hurt others and us just to avoid the messier truths of reality.

***

On climate science:

Someday, I hope we realize the full extent of our interdependency with the planet. It may be our best metaphor for our connection to the divine, right down to the way we disregard it at every turn.

Binary (De)code

A distillation of some larger thoughts:

Faith. I do not think that word means what you think it means (thank you Mandy).

Certainty is the religion of the day, and it cuts across a broad swath of congregations. Some are utterly certain of their version of God. Some are utterly certain that versions of God mean there is none. Some are utterly certain of the material world at the expense of the spiritual. Some are utterly certain of the Spirit at the expense of the material experience right in front of them.

It’s as if doubt is the toxic influence in culture. I’m fairly certain that’s not our problem.

***

The so-called division between science and faith is not so much a debate as a mutually assured form of keeping oneself from fully engaging either. Both ends of the spectrum of voices that take up this form of rhetorical trench warfare do so at the expense of their own legitimacy in claiming answers of certainty in the face of the unanswerable. That is neither the scientific method nor legitimate faith. Then again, humans do have a way of claiming a sense of rock-solid certainty without earning it in any meaningful way. Maybe the better path comes from allowing both to wrestle with mystery rather than fabricate an exclusive, totalizing certainty. Maybe the better path is to always remain conscious of the maybe.

Songs that Sing Us

Every single person should actively seek out that songwriter whose lyrics speak his or her life. Not songs we admire or appreciate or even love. These people write songs that feel like our own thoughts, but better or clearer or more useful than we could make them ourselves. We don’t listen to these songs. We remember them before we’ve ever heard them.

I’ve found mine. Grew up in the same town as him. That’s likely one of the reasons I love his work so much. But more, in his lyrics I hear the same wrestling match I find myself in. Doubt and faith. Anger and grace. Fear and resistance. More questions than answers. In it all, however, there is a hope that refuses to be anything more than present, even when it feels like it shouldn’t be. Sometimes, it’s as if I’m hearing his side of a conversation the two of us are having. I’m pretty sure that’s the greatest compliment I can pay his work.

I hear people say all the time that a particular artist inspires them. Moves them. Challenges them. I say, look for a writer whose words feel ultimately familiar and foreign in the same moment. And let them take you to church.

***

Nostalgia alert: I miss songs with space in them—solos and silence and moments when we weren’t necessarily waiting for the next line.

Anti-nostalgia alert: That doesn’t mean that every song with space built in earns it. I’m looking at you prefabricated 80s metal bands with paint by the number guitar solos and ridiculous electronica/house/sample-recyclers who think the mere act of looping is art.

Double nostalgia alert: I miss when making enough good songs to warrant an entire album was mainstream.

Double anti-nostalgia alert: There are so many artists who should never make another album. Just keep making singles until your 15 seconds pass.

Harry Chapin

I hear people say all the time, “We didn’t really expect (insert child’s or children’s name[s]), but now I can’t imagine life without him/her/them.” I’ve said it myself, about all three of my beautiful children. But I’m lying when I say it and selling my imagination short. Of course I can imagine life without them, and in many ways what I see looks good. Looks easier. Looks less complicated. Looks better in some very tangible ways.

And this is how I know I really and actually love them. Even in the moments when I shouldn’t, when it would not be selfish not to, my love for them persists. In a sense, it really isn’t “my” love at all, I guess, but something greater that comes from outside of me and I am grateful for it; I am grateful for them and the ways I would not be me if I were “just” me.

***

I think we almost always know when we are taking something for granted, despite our protests to the contrary. It’s actually thinking about what we’ve lost by doing so that sneaks up on us—the feeling of responsibility we allow busyness to push away until we can no longer ignore it. But I’m certain it’s better to feel that guilt and shame than it is to lose what it is we took for granted in the first place. Unfortunately, there have been too many times when I’ve hoped that my children will agree with me when they’re older. And my family members. And my wife.

Semicolon

My deepest wish: that love would outweigh rightness, and rightness will stop being confused for righteousness.

***

An essay like this does not end. Tomorrow, I may come across a new passage in an old book that upends my understanding of any one of these thoughts. Or maybe my next hike will lead me around a bend on a trail I haven’t walked and the view I discover will shake my notions of what I know. Maybe my children will grow up to change the world in ways I’m not even aware it needs to be changed. Maybe I’ll finally get that book contract or maybe I’ll never come close.

I don’t know. None of us do.

Then again, I’m the guy who didn’t think he’d be alive to write an essay looking back on 40 years of living. How’s that for a clichéd ending?