WRITING AFTER SUNSETS

For years, I maintained a separate blog called writing after sunsets as a place for my thoughts on writing, reflections on teaching, and an outlet for writing that matters to me in ways that make me want to control how it is published. It has also been, from time to time, a platform for the work of others I know who have something to say.

Now, with this site as my central base of online operations, I’m folding that blog into the rest of my efforts. All previous content is here for easier access, but the heart of writing after sunsets remains in both my earlier posts and those to come.

On the Death of Rashaan Salaam

The news came in a text first. Then a couple tweets filtered into my timeline, the first from ESPN’s Adam Schefter.

Rashaan’s dead. I guess as you get older, these moments happen more often. Mortality does not discriminate, and when someone like him dies, the rest of us, if we’re paying attention, take personal stock. At least for a moment.

When I say “someone like” Rashaan, I think that’s what’s kept him on my mind for the last 24 hours. I’m not going to claim we knew each other more than we did, which was to say we had a passing acquaintance as guys who ran track in the same league, though by virtue of talent, that league was not actually the same.

The most extensive conversation I can remember having with the guy was about the relative merits of the song “Check the Rhime” on A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory while we waited for a race to get called.

The thing is, Rashaan exists in a weird space between someone I knew and a hero, two boxes I would never place him in. Rather, he exists between, a shining satellite I came into orbit with simply because we ran that same races. That seems to be the case for many people trying to make sense of how he died.

He was neither my peer, nor my nemesis (that honor is taken by a guy named Ron Allen). No, I’d have had to have been faster for that to be the case. Because Rashaan was fast. Really fast. But that’s not the part of his story that gets told.

In the pre-internet world of the early 90s, Rashaan was an eight-man football phenomenon who drew national attention without the aid of YouTube, Vine, or the high school scouting apparatus that exists now. And it was warranted. Dude was crazy.

In a game against my high school, he ran a sweep to the left and one of our best players hit him perfectly below the knees, kicking his feet up over his head. Normal runners are happy not to have been injured by a hit like that. Rashaan put his free hand on the ground like he was doing a handstand, swung his legs back underneath himself, landed on his feet, and ran another 30 yards on the play.

What?

And that was not atypical. But I didn’t play football. So, when he went from tiny La Jolla Country Day to the University of Colorado Boulder to the Heisman Trophy to the Chicago Bears in the first round of the NFL draft, I watched as I had in high school: impressed to have seen him in person but not quite a fan, because he played for the other team.

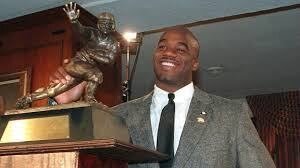

Rashaan with the hardware. Image from ESPN.

Lost in the high school football legend and the perception of his unfulfilled pro potential is the fact that Rashaan could fly on the track. He wasn’t a pretty sprinter, like Carl Lewis or Usain Bolt. He ran like that yoked-up guy on the field, just faster without the pads to slow him down, as if he needed the unencumbering.

If he hadn’t been running in San Diego, in the early 90s, he’d have been touted as one of the fastest guys in his region. Unfortunately for him (and more so for me), that stretch from 1990 to 1998 was a golden age for high school sprinters in San Diego.

For a little context, Rashaan ran a 10.8-10.7 second 100 meter dash. That’s blazing. That kind of high school speed translates to a Division 1 scholarship for many runners (and could have for him had he wanted to focus on track). But that made him one of the second-tier runners when it came to the guys around him.

Guys like Darnay Scott (10.77), Johnny Robinson (10.77), Paul Turner (10.49), and Vince Williams (who would go 10.45 in 1996) all prevented him from being seen as a premier sprinter, not to mention the six other guys in the section running under 11 seconds I haven't named. And then there was Riley Washington, who still holds the CIF state meet record with his ridiculous 10.3 obliteration of the previous mark and the seven fastest guys in California not named Riley.

San Diego was home to several high schools that seemed like speed factories when I was coming up—Morse, Kearny, Lincoln Prep, Southwest, El Camino to name a few—so Rashaan’s freaky speed was, well, kinda ordinary in an extraordinary era. To get a sense of this, check out the 1991 state 200 meter final here, with Darnay and Riley in the race NOT winning.

But let me assure you, there’s looking at a runner’s time on paper, there’s watching them stop the watch on the screen, and then there’s the peculiar sense of having that speed imposed on you by someone who’s just gifted in ways you are not. That’s my clearest memory of Rashaan Salaam.

A brief bit of history, when Rashaan was a junior and I was a sophomore, I ended up running the open 400 against him at a meaningless dual meet . For the first 250 meters, it was very much like he was running and I was barely moving. But I’m fairly certain he was not training for the 400 at that point and he broke down physically, hitting what runners call the wall not once or twice, but three times, allowing me to reel him in and cross the line in a virtual tie.

Reminder: This was a meaningless meet. He would still go on to win the Heisman. I would never reach the CIF meet in the open 100 (his race). I only slightly celebrated in the moment, knowing that if he had cared at all or put in any time training, he would have smoked me. Then I forgot about it.

Apparently, he did not.

The next season we ended up in the same heat of my race, the 200 meter dash. As a junior, I was running just outside fast enough to make the open field at CIF sectionals, but just inside fast enough to end up in races with guys like Rashaan and Darnay. It was, as I’m sure you can imagine, not good for the ego.

This was the first time Rashaan and I had run against each other since the 400 the season before. What happened, I’ve never forgotten.

Rashaan started in lane two while I was in five, which meant I had a stagger of several meters when the gun went off. Also, I was stronger at the tactical thinking of running the curve than the brute speed of the straightaway. And, for once, I came out of the blocks quickly, which was unusual given my relatively tall 6’3” frame.

None of that mattered. The moment I was up and running, all I could hear was the sound of Rashaan’s feet striking the track once for every two strides of mine and his grunting with each footfall. He made up the stagger in the first 20 meters and THEN put the hammer down, rolling past me like I wasn’t even trying. It felt like he picked up a stride on me for every two I took, and no amount of digging deeper made any difference. With 50 meters to go, he was so far ahead he could have jogged the rest of the way.

I wish he had.

Instead, with 20 meters left, he turned and ran backwards, staring at me all the way through the finish line. I crossed about a half of a second later, but it might as well have been a year. I swear, it felt like he had time to pop a soda before I got there.

And that was it. No handshake or high-five or acknowledgement of any kind beyond the utter thrashing he gave me on the track. I only ever saw him again in the 4x100 relay (which we won). And then he was swallowed, by football first, and time after that. I hadn’t really thought about him much recently save on the rare occasions I ended up reliving my track days with old friends.

At least, that was true until yesterday, when they found his body in a park in the Boulder area, the one place he seemed to have been happy, or so I’ve read.

That’s the thing about guys like Rashaan. All we really know about them is left in that 21-second race, a quarter century ago.

New Short Story

Hey all. My short story, "Crossover," is out today in Angel City Review. Here's how it opens:

Nobody beat Ancient Jay to the court on Saturday. Billy knew this was true. He’d tried four times, once setting his alarm so he could get there before the sun came up over the houses on the hills that horseshoed Glen Park. It didn’t matter. Jay was there first.

Ancient Jay wasn’t really ancient. Probably late-thirties, forty tops. People called him ancient because he’d been playing pick up ball at the Glen longer than anyone else and because of his face. His sun-browned skin was creased like moist smoked jerky. Worse was the way Jay sweated. His pores were like little mouths drooling salty ooze that dribbled more than dripped. They never played shirts and skins and most guys called it the Jay Rule to his face. But Ancient Jay was a part of the park, constant like the swing set or sandbox or cement path winding through the two acres of grass and trees that smelled like pine and Pacific when the breeze blew through from the beach just across the Coast Highway. So the stories grew up around him. Billy knew the morning Jay wasn’t there would feel like someone took down the monkey bars and left up the slide....

You can find the rest of the story, and all of the stellar work in the winter edition of Angel City Review free at http://angelcityreview.com/.

A Roadmap or a Vacuum

I teach writing. Even when I'm teaching literature, I'm teaching how it was written as a way of seeing why it matters. Words matter to me, because they're never—never—just words.

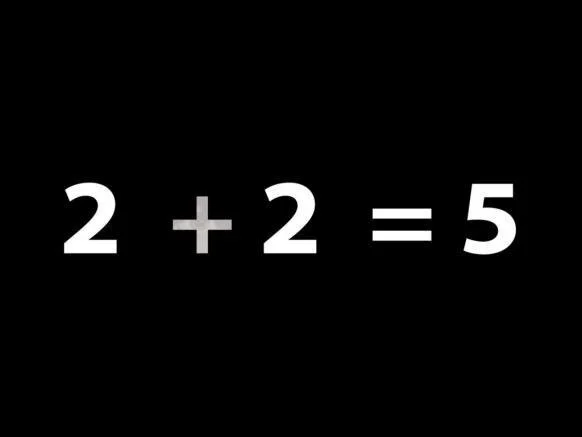

A simple message of hearing and speaking critically is this: never view rhetoric as empty. How people argue their point is never merely an intellectual construct. It's a roadmap or it's a vacuum.

When you line up what people believe with why they believe it, you get one of those two possibilities in terms of how you can assess where their thinking will take them. Remember, words are never just words.

In some cases, you can see how an argument will play out in action. The sources and, often, the fallacies an arguer draws on to claim authority carry in them behaviors and message shapes the careful listener will find instructive in anticipating where this will go.

Hence: roadmap.

Example: Your friend tells you about a time a person of differing political views tore up a political sign they had posted in their yard. Your friend then points you to four separate Facebook posts describing similar behavior from "the same type" of people and, without pause, uses that in addition to their own experience to characterize all people they suspect as holding even similar political leanings as (fill in the negative characterization most employed by your friends/family/neighbors).

This, as we say in the business, is a fallacious two-fer. The first is the logical mistake of extending one's own personal experience too broadly in relation to the complexity and diversity of experiences found even in the limited world of yard sign destruction. Your friend's story becomes broad proof of their own feelings about "those people."

But everyone, even the most stubborn individualists, know their story isn't enough. Thus the second fallacy—a carefully cultivated mechanism for bias confirmation—becomes important. By linking to a few other friendly examples/perspectives, their own assertions are validated exponentially (in their heads, anyway). And that gives the confidence in their sweeping (and almost always wrong) generalizations-as-facts views.

And this becomes your map. This person will make their own opinions a truth stretched across an issue and act accordingly. It doesn't always tell you what they will do, merely how they will justify themselves after the fact (and yes, that is as scary to type as it is to consider in practice).

But a map is always better than the other option: the vacuum.

Taking the same sign vandalism, the vacuum rhetorician tells you the story and says, "That was wrong, the people who did it are bad, and I will never trust them again." And that's it; they've built a solid wall of certainty you can't see through to their reasoning.

These are not logical structures, they are the results of submerged processes that could hinge on all forms of fallacy or irrationality or even deep bias. But who knows, because this is the rhetorical equivalent of a kid responding to a math problem without showing his work. Right or wrong, you have no idea how that kid ended up where he did.

That's the vacuum. In terms of a math problem, it's confusing and counterproductive. In terms of the sign vandalism, it's problematic.

In terms of where we are in America today, it's terrifying.

Post-Election Conversations…

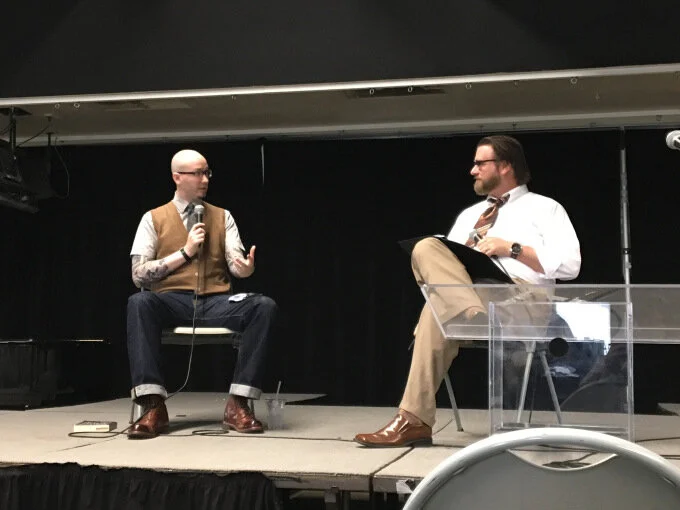

Photo Credit: presbylutheranism.com

A follow up on yesterday’s post. You can find it here.

I went to bed last night knowing that my son’s fears had been realized in the election, and also that he didn’t know yet. I found him sleeping in our room again because of his agitation.

I didn’t sleep well, and then my alarm went off. He wasn’t even fully awake when he asked:

“Who won, Dad?”

A note before pushing on: this isn’t likely to go where you think it will.

I answered honestly and held him as he tried to figure out—out loud—what it means now that what he was afraid of is real. I did the same with all three of my kids. It was a tough morning.

Here’s what we have decided so far. This election is over, but its challenge is not. What has been exposed by the process is ugly, but ugly has always been with us. And there is no option of checking out as if we bear no role in responding to what we see.

So we will:

choose hope over despair;

look for those who are hurting or afraid and respond with love;

listen to what to the words and stories of those who are usually silenced;

speak truth into the vacuum of bias and division we live in;

refuse to limit who we are because of who others want us to be;

and refuse to allow injustice to pass in silence.

If there is a mandate in this election, it’s that this country needs to find its heart. If we do, we need to use it rather than guard it. Ours is the sin of believing the world can only be only right when it resembles our version of how it should be. The suffering that myopia causes and has caused is enormous.

I’m looking to atone out loud for the sake of my kids and my country.

Post Script: Two incidents of note happened after I finished writing this that I think speak to what I’m working on here.

First, when dropping my sons off at school this morning, my parting words were, “Choose hope and look for people who need help.” As they walked away, another parent pulled into the loading zone and as his kid got out I heard, “You tell people how wrong they were and how Donald Trump made those idiots see.” They both laughed.

And second, I’ve already heard from six students trying to figure out how to understand their world in light of this paradigm shift. All have been openly harassed this election season for the color of their skin or their sexual orientation.

If you have said, “Make America Great Again” at any point, start by fixing these.

An Election's Eve Note...

I shouldn’t be writing this. I have other things to do. And yet…

…last night I walked into my bedroom to go to sleep and found my son curled up on the floor next to our bed. On our covers, he’d left a note.

“Please don’t move me….I’m worried about what will happen tomorrow.”

That’s not the whole thing. You don’t need the rest of his fears about today’s election.

You need to think about the role you’ve played in them.

My boy is nine and deeply empathetic. He gets it from his mother. His antennae are more sensitive than most, his words incapable of capturing yet what he’s picking up. But he’s catching our transmissions. And he’s drowning in what we all know about these politics as unusual.

We’re not ok. We should be worried. And we should be better.

The characters we should be impugning are our own. The values we should most fear have been on full display. And the fear in my son’s note is right now our legacy.

I’m old enough to know our country will move on after the votes are counted and that the terrifying shit show we need to address as a culture began well before the clowns took over this particular rodeo.

But what I think my son in most scared of is the conclusion I’ve come to at the end this long national failure of character.

We lack empathy. All of us. We can’t see each other.

How many think pieces on racism, classism, sexism, partisan-ism, and dogma do we need to see we’re growing increasingly blinding to who we’ve become?

How many polls results do we need to see the grand canyons we’ve so willing dug between ourselves?

I wish I felt more hopeful today, had some semblance of civic pride. History will be made one way or the other. But no candidate can step into the void we’ve created inside ourselves. No law will begin the hard, generations-long work needed to draw us together in ways we’ve only ever experienced in faulty rhetoric and nostalgia.

And no amount of worry on our part will fix this either. Worry is why we’re here in the first place. Worry about ourselves, our needs, our wants, our place. We won’t share because we’re convinced only we can see the world and what it needs clearly.

Clearly, we cannot.

Consider my son as I have: one small canary in a coal mine we should have abandoned long ago.

Go ahead and vote your conscience. But make sure you’ve found it first.

My interview with Ryan Gattis via the 1888 Center podcast, The How The Why

New Today: The 1888 Center's podcast, The How The Why, has posted my spring interview with Ryan Gattis regarding his novel All Involved. In it, we talk creativity, L.A. fiction, community, and maybe the Donut Man. Give it a listen here.

writing difficulties...

An observation:

Writers make difficulty by design. At least, the ones who make the most sense to me.

An explanation:

Writers, it seems, must find complications in life in places they could, ultimately, ignore if they weren’t cultivating a sense of struggle. Some might call this a pose, an air, a mantle tossed over their shoulders to approximate weight they don’t always actually carry. To be sure, writing is to accept a very privileged position in culture: an intersection of time, affluence, attention, and the assumption people need and want the results of those three things. Toward that end, they complicate living.

A (personal) metaphor:

This posture is faintly akin—metaphorically, of course—to the act of cutting, though not as externally damaging. Life is not controllable, and those things I actually cannot control are much scarier than the affectations that accumulate in my collection of what makes me “difficult.” Small phrases like incisions applied with precise control dissipate my unimpeachable sense of being unable to stop the world’s spin when chaos threatens to swallow me.

An amplification:

The world screams for our attention, to grab us by the ears and eyes and skin and impose itself. It seethes through broken teeth curses in broken children sold to satiate its anger; in hate masked as “common sense” and “heritage;” in losses made invisible by the uniquely human desire to turn away in order to protect our comfort.

A diagnosis:

However, good writers—by nature and by nurture of difficulty—cannot turn away. They need not even see the whole picture in order to extrapolate out the worst of cases in the best of circumstances, but they keep looking anyway. It’s their gift, if one can call it that. More, it is their responsibility.

A prognosis:

The cost of that privilege is so often a writer’s self-imposed debt.

I write because maybe.

“Why write? As soon ask, why rivet? Because a number of personal accidents drifts us toward the occupation of riveter, which preexists, and, most importantly, the riveting gun exists, and we love it." —John Updike, "Why Write?"

Why a person writes is something they should consider and, ironically, write about. Every so often, we need to remind ourselves why we need to string our words and dreams into something more.

This is an exercise I have all my students take part in, and, I guess, something I haven't done in a while. You can see my last attempt here. So here's my current answer to the question we all need to answer: Why, with all the other options we have, write?

I write because I breathe. When I breathe, I exist. When I exist, I understand that others exist. And when I understand others exist, I want to know them.

Or, maybe, I write because I can't know them. Not in a way I want to. Not in a way that moves beyond limited interaction. Not in a way that makes them real.

Or, maybe, I write because real is so illusory. It shifts at the exact moment I reach out to grab it. At just the moment I see it clearly. At just the second I've chosen the right words.

Or, maybe, I write because it really isn't a choice. Words are compulsion. Words are affliction. Words are skin, once torn, growing slowly back together.

Or, maybe, I write because living is the wound and stories my salve. My bandages. My scabs before scars destined to be their own stories.

Or, maybe, I write because my scars are not enough. They are just my own. They are just my sins. They are just my fault.

Or, maybe, I write because my faults are not their faults, but their faults make me human when I hold them next to mine. They make me aware of my imperfections. Aware of their human character. Aware of the fact that our humanity is bound up in these.

Or, maybe, I write because humanity is lost on humans until we arrest it in the amber of words. Grab it with the swipes of my pen, the strike of my fingers against the keys, the frozen flat surface of the printed page that captures my heart in ink.

Or, maybe, I write because that capture is the only real metaphor for freedom we have. Illogic as sense. Impossible as practical. Walls as open windows.

Or, maybe, I write on the very walls I want nothing more than to transcend. Maybe those words are my climb. My scale. My ascent.

Or, maybe, I write because there is nothing left to ascend save the holy moment of knowing my unknowing at the moment it ceases to lead only to the unknown. Doubt transubstantiated. Fear crucified. Hope resurrected.

Or, maybe, I write for precisely that maybe. That open question. That expansive possibility. That known unknown.

I write because maybe. Maybe.

until we are all free...

A note on this post: the content of my thoughts in this post comes in response to the wisdom of the people of color in my life (a group that includes people I’ve never met, but whose work in writing their experiences and perspectives has broadened my notion of everything). Nothing I’m saying here hasn’t been expressed by others. I am indebted to their contributions, as I would not see the water we swim in as clearly without their help. This is merely a space for me distill some of my own thoughts on the matter. I hope they challenge you as they do me.

As a parent, some of my most difficult conversations revolve around trying to help my daughter find her place in this world. Case in point: our recent discussion about how the Constitution was not written with her in mind at all.

My daughter is a young black woman, which is a precarious position in our society. As she becomes more aware of the history of her adopted country, she has to come to terms with something I never will. At the inception of America, in its most prized and lauded documents, she was invisible.

Because she is black, she was not afforded full personhood. Because she is a woman, she was even further erased. This is the reality of our nation’s origin story.

Unfortunately, that reality is not merely an artifact of the past. In many ways, my daughter, radiant as she is, must still fight to be visible like most women of color. And that fight, as she is learning from the cycle of violence that plays in our nation on repeat, is not merely rhetorical.

To live in America is to live in a tension between the idealized and never achieving that ideal. It always has been. For some, that tension is intellectual, a form of disappointment that things aren’t “the way they should be.” For others, however, the cost of being caught between the dream of American possibility and the reality of its brokenness is violence, fear, and, in too many cases, death. This, as much as anything else, marks what we now commonly describe as privilege.

The divide between these two cultural experiences is that we live with a nostalgia for something that never existed, a type of historical storytelling that has often been a form of violence employed for the sake of preserving one group’s sense of itself at the expense of—and often through the complete erasure of—another group: their identity, their agency, and their lives.

Do you ever wonder why a criminal of color is so easily cast as representative of his entire racial or ethnic or religious category while a white man who commits the same crime is solely responsible for his actions? Do you ever wonder why you never wonder that? Again, this is what people mean when they ask you to check your privilege.

An example: the political slogan “Make America Great Again.” To adhere to this notion, that there is a historically better America to return to if we just try hard enough, is not new. The current candidate slapping the phrase on ugly hats did not originate the idea.

It’s always been with us; the elusive sense that returning to a simpler time would soothe today’s troubles, would save us. It’s why so many movies in the 80’s sought solace in taking us back to the 50’s.

But this is only a solution if your proximity to the Great American Tension allows you to see that earlier time as safe. As my pastor, a black man, put it, “What part of the past do I want to go back to? When was it better here for me?”

Again, if this perspective has never occurred to you, yours is merely an intellectual tension. If you don’t look at our history and recoil at the very real danger of the internment camp, the lynching tree, or the reservation, you long for a time that only more fully and openly privileged a very small group of people: a group you may not have been a part of even as you imagine yourself being so.

This is my problem with people who default to the unflinching rhetoric of valorizing without any criticality the work of the American Founders. Yes, they wrote documents laden with immense potential to liberate humans and create space for equality that has never really existed.

And yet, they lived lives that directly undercut the potential of their words and blocked the path to the very equality they championed for so many people in this country. In essence, they proved that even implements designed to heal and empower become weapons when they are applied selectively to benefit only those we most resemble.

And to create these benefits, we have kept them from others time and time again, right down to our three most cherished freedoms: the pursuit of happiness, liberty, and, in far too many violent instances, life itself.

This is why “I can’t breathe” are not merely a man’s dying words. This is why we should not fall victim to the pandering sentiment of “Make America Great Again.” And this is why we should never say #AllLivesMatter, because we don’t live that way enough yet to claim it as our aspiration.

Instead of nostalgia, which has literally killed people, we need hard reality, honesty that does not flinch or recast the world in ways that make us feel better about ourselves, justice that is not selectively employed, mercy for those who are begging for us to acknowledge their suffering, and an actual attempt to hear each other in the midst of pain that renders us deaf.

I actually believe in the potential of the principles our country was founded on. If applied to everyone in equal measure, this would truly be the great place we imagine it to be.

But that’s not our reality and will not be until we do what neither the Founders, nor any generation since, could: value equally the humanity of everyone and admit that we are part of the blindness keeping us from doing so. This is the American greatness I want my daughter to experience.

Word G(r)ift

I had to drop some books off in my office* the other day, an occupational hazard of the job. Books find me, I swear, I don’t go looking.**

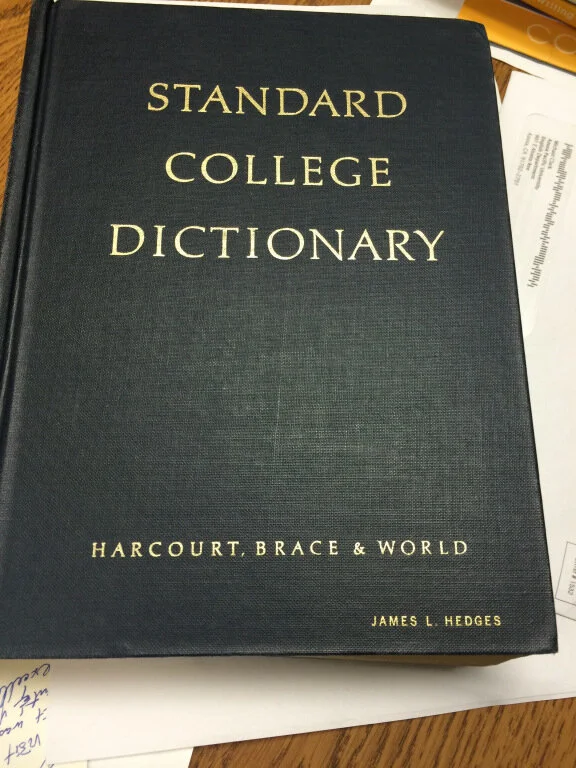

I had no intention of staying in my office any longer than necessary because that’s how work you weren’t planning on doing attaches itself to you. But as I turned to go, I noticed an older looking book I didn’t recognize sitting in the center of my desk.***

Upon closer inspection, the cover read Standard College Dictionary with the name “James Hedges” pressed into the lower right hand corner. This was odd. Dr. Hedges was the chair of the English department I now teach in when I was an undergrad, but he retired well before I was hired back as a professor.****

Side note: The at that point unknown gift giver had no way of realizing how appropriate his gift was. When I was six, I went on vacation with three books: an Archie comics collection, The Black Stallion, and Webster’s English Dictionary. I read every word in that dictionary before we got home. My family still finds that funny.

Flipping the book open, I found a letter tucked inside. In short, another former professor and now retiring colleague from the Communication Department, Dr. Ray McCormick, was leaving me the dictionary as Dr. Hedges had given it to him when he retired.

The note is simple and, in McCormick fashion, devoid of unnecessary emotion. As my rhetoric instructor, he emphasized that while form is message, our message must be true and useful. These were our guidelines. And yet…I can’t help being moved by his last line.

“On your retirement, pass it along to the next guy!”

There’s a certain sense of validation in the assumption that I’ll make it to retirement in this field. On the surface, it’s a small note to be sure. But Ray knows me; the confidence written into that line matters to me, as do the other votes of confidence I have received from time to time from former professors-turned-peers.*****

They remind me to look for ways I can call out talent and potential in my students. One day, I’ll likely be handing one of them that old dictionary with my own note in it.

Notes:

* I still find it immeasurably weird that I have a job that provides me an office to go to, which makes the gift I found on my desk even more touching.

** That is a categorical lie. I’m always stopping myself from buying books.

*** Which did not automatically mean I had not put said book there, merely that I could not remember doing so. As it turned out this time, though, I had not.

**** This turn of events monumentally more surprising than the whole having an office deal.

***** One of the gifts and oddities of working at the school you graduated from…