WRITING AFTER SUNSETS

For years, I maintained a separate blog called writing after sunsets as a place for my thoughts on writing, reflections on teaching, and an outlet for writing that matters to me in ways that make me want to control how it is published. It has also been, from time to time, a platform for the work of others I know who have something to say.

Now, with this site as my central base of online operations, I’m folding that blog into the rest of my efforts. All previous content is here for easier access, but the heart of writing after sunsets remains in both my earlier posts and those to come.

No Such Thing As an Easy Hike

Thin air makes for some fantastic views. It also makes for some rough walking.

So, this is me, standing on top of Grays Peak in central Colorado. At 14,278 feet, it's the tallest point along the Continental Divide and the 10th highest in the state. And if this were my Twitter or Instagram feeds, this is likely where the story would stop. Me. Smiling. My second 14er topped.

Like every story, though, there's a lot more to this hike that makes it matter. In fact, while summiting was great, getting there was often terrible, which is why it's worth doing in the first place.

Hiking a mountain is never easy. A year ago, I thought I might not be able to do it anymore. I took a trip last-minute, without preparing enough, and tried to do too much. In most cases, that would have meant burning out, not being able to do the best part of the hike, and some embarrassment (all three of which occurred).

But it's what happened to my heart that had me questioning whether or not something larger was going on inside of me. Long story short, in the middle of trying to hike Half Dome in Yosemite there was a four-hour stretch of time that day where things went all sorts of sideways on me, a long, slow hike out that was way worse than I let on, and then a few months of serious worry on my part.

We started the Grays hike in the dark. I'd be lying if I said my worries didn't follow me all the way to the summit.

After putting it off too long by pretending I was too busy, I did my due diligence and had the doctor check out my heart. The scan and blood work said the ticker is in working order. But there are some other issues that I need to address.

Of course, that meant finding a very difficult hike and acting like completing it would be no big deal. This is the problem when sarcasm is your love language. Even I sometimes forget I'm being ironic...which is...ironic...

So I picked an arbitrary hike in Colorado where my wife's family lives—the much more difficult Longs Peak ascent—and asked some people if they wanted to do the slow climb with me. My brother- and sister-in-law hopped in and I'm glad they did, and not just because they helped me avoid the mistake of making Longs my first big attempt since my heart issue (though I'll be back for it at some point).

My hiking partners for the journey.

Rather, knowing they were going to hike with me was motivation to get myself ready. It helped me to get in the training I needed because I've always been motivated by making sure I don't let my team down.

And, when things were really difficult for me on the trail—the equation altitude + self-doubt = no summit is much harder to solve alone, regardless of the variables—they patiently encouraged me to take the rests I needed and see the progress we were making. It's no exaggeration to say I would not have made it up without them.

Along the way, this hike did what most really good ones do: it forced my desire to complete the hike and my fear that I couldn't surface together and made me sit with them for the entire hike. And not in some metaphoric way. In tangible, literal moments I was faced with deciding whether or not I wanted to or even could go on.

The saddle between Grays and Torrey's Peaks. This view comes a long way up the trail and served as a stark indication of just how far we had to go well after I'd already had a few moments of serious doubt.

That's the best thing about hiking. It's not the metaphor people want to make of it. That's the talking about the hike we do after the fact (some of which you might just see me doing here later)

Hiking, especially when you don't do it as often as you might like, merely communicates what it will. It tells you that you're heavier than you should be. Or you're not in as good of shape as you thought. Or you're too goal oriented to appreciate what it has to offer. Or you're not as self-assured as you tell others.

Of course it can remind you of good things in life too. That's the point. Like so much of living, a serious hike is capable of inducing all elements of the spectrum of human emotion, and not always along the same trails.

Often, the best elements of the hike come from how elevation provides clear evidence of the progress you've made. While I'm walking, I'm often completely focused on the next step or two. I find it's the best way to avoid falling off the mountain. But it's also an extremely effective way of not having a grid for how much you've actually accomplished to that point.

Speaking of looking back, you can see the trail snaking along to the right of the ridge line in this view.

It is important to look back from time to time, physically, and view the trail you've covered as it unspools behind and below you if you're going to complete what's left of it in front of you.

It's also important to watch for the elements of the hike that are unique to that specific trip. A lot of hiking is the same. Follow the trail. Hydrate regularly. Eat enough to keep going but not so much you create problems on the walk. A lot of the work is standard.

But every hike, even the ones you've done a number to times, is going to give you something you haven't experienced before, whether that's internal or external. On this hike, it was goats. Literal ones of the mountain variety. An entire herd of them marching single file down the ridge line just below the summit. They were a small message: we were visiting someone else's home and should behave accordingly.

My friend says these are animals are the greatest of all time.

Then we rounded a switchback and saw a mother with her kid, both nonchalantly grazing, undisturbed by us or the altitude, just doing what I assume mountain goats do with or without an audience.

Their appearance was a solid reminder that I needed to do the same. Regardless of the people on the trail, I needed to do what I came for as long it felt like my body would allow me to do it.

So I did it. And it didn't get easier just because a couple of goats made me feel like I was being to sensitive about every stray increase in my heart rate or fear that I'd be letting people down if I turned and headed back down. In fact, it got even more difficult at some points. Rather, those goats were one part of the process I needed to go through to get more than just some excellent photos of the stunning views from the top of the mountain.

One of said views from the top.

For me, this hike was mostly painful in the best possible ways because it helped me find something I thought might be lost.

It didn't show me I'd regained the ease that went with hiking in my youth. Pretty sure that ship has sailed and probably sunk.

It didn't reveal some spiritual secret I'd been missing in the form of a metaphysical push up the toughest sections of the path or the emergence of a well-timed goat.

And it didn't trivialize the process with a trail that made it easy for me to feel like this was an accomplishment of my own.

From this view, a mountain can look impossible to climb. But the reality: this peak is more than a thousand feet lower than Grays.

Rather, this was a literal exercise of regaining the trust that must be placed in the intersection of the path I walk, the preparation I've done, the willingness to struggle I engage, and the people I let in who are willing to walk with me.

All of those combine to make mountains that seem unclimbable from the bottom feel inevitable from the top.

On the Capital Gazette Murders

Photo Credit: Ian Keefe - Unsplash https://unsplash.com/photos/lPUe2AHwajw

On June 28th, five journalists were murdered and scores more hurt in one of America's most prevalent cultural products: a mass shooting.

After thinking about what happened the whole day, I threaded some thoughts on Twitter and ended up getting interviewed for a story on the threats journalists work through. You can find that article here.

It's a good piece, but what drove me to put my own experiences in public is more complicated than what showed up in the article. So I'm putting the thread here for anyone who might be interested.

I meant to post a week ago, but life is busy and, well, sadly, I feel fairly confident that we will be in this position again, trying to come to terms with the collective trauma of yet another mass shooting.

Below, then, is what I wrote at the time:

I caught the news of the #CapitalGazetteShooting while driving home from family vacation and have been turning it over in my mind since. A few thoughts to thread here.

My first career was close to five years at a local paper east of L.A. that is similar in many ways to the CapGazette. Our crew was small, though bigger than it is now. This was the late 90s and the bottom hadn’t dropped out of local print yet. When I started as an intern at the paper, one reporter told me I wasn’t a real journalist until I’d received a death threat, something that didn’t happen until a year and a half later after I’d been hired on full time. He took me to lunch after and we (sorta) laughed about it.

We didn’t take it lightly. But it was a part of the job. Sometimes, people didn’t like what you’d written, not because it was false but because it was true, and they would lash out. I covered mostly education and business in my time and even I got threats from time to time. But you rolled with it. Put it out of mind. Watched yourself if interviews went bad, but otherwise didn’t see it as a credible fear. We had a job to do, hard questions to ask, and unpopular stories to write.

We also lived and existed locally, part of the community we covered. That meant sometimes people knew us. Saw us outside work and told us off. But we were still part of the world they lived in.

Now, however, the world has expanded and the threats are very, very different. I’m out of the business and still troubled by the shift that’s happened. Today, people like Milo Yannopolis say things like vigilantes should hunt down journalists. But when they make these threats, they’re not using a bullhorn. They have the power of a digital network connected to a sea of like-minded people who don’t read nuance into their words.

And let’s be honest: Milo wasn’t nuanced. He was, like he always is, looking to profiteer on hyperbolic statements he knows are dangerous. That’s his brand. Shock and awful. The sad thing is, his brand sells to a certain reader who sees the world as needing a violent fix. It’s a brand Trump has given so much legitimacy to in the past two years that it seems patriotic—to some—to consider journalists a threat rather than a necessity. As an existential problem with elite roots and dark forces driving it that only a racist can see.

What’s missing is the humanity of people doing the job, and that’s intentional on the part of the Idiot-in-Chief and people who pander to these false representations to consolidate power and influence over those who want the press to be part of the same conspiracy they feel is at the root of what’s wrong with America. Unlike the local problems I experienced as a reporter, where someone who read my articles was responding to something in their community, this is different.

The poison in our national discourse is bringing larger issues to bear in local settings. And the call to violence—the encouragement to it, actually—is pervasive. It’s direct. And it’s blood on the hands of people who see it as merely politically and financially expedient to traffic in stirring the pot of anger towards actual harm.

Of course I’m not saying that this was a situation where some Mephistophelian voice used a social platform to whisper in this shooter's ear. That’s stupid and the real situation is worse. Rather than one voice, there are thousands. And they’re not whispering. They’re shouting. Pleading for people to forget the humanity on the other end of their gun’s sights. They say it’s just rhetoric. Figures of speech. But it’s not. It’s an avalanche of hate. And it’s killing people.

In this case, the victims are journalists who were doing the kind of work we need. Holding us accountable. And maybe that’s just it. Accountability is threatening to those who think like this. So they invert that threat with violence. Just not with their own hands, which they think are conveniently clean of the blood that gets spilled. But they are not. And I grieve that this, like most other mass shootings in America, won’t likely to anything to stop the cycle that causes them in the first place.

My Black History Reading List

It started, as all these situations do, with a stray comment on a stray Facebook post. The post conflated Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling for the National Anthem before NFL games to protest police violence against communities of color with the idea that he was being offensive to veterans. Pretty common stuff for that period.

And then, someone disagreed. My wife, to be exact. Pointed out the nature of the protest in Kaeprnick’s own words and the racially problematic nature of the third verse of the Anthem. Some discussion ensued and then, with the proverbial theme music, in came a guy (not the poster, who took a couple days off of Facebook after posting) to clear up how wrong-headed and ignorant anyone not agreeing with the post were being.

You know the guy. Keyboard Hero™.

Dude trotted out common sense and moral failing and “you’re upset because I don’t agree with you” with no actual discussion of the comments he’s “responding to,” just half-assed, unsupported assertions of his rightness.

So I dropped in and try to get a sense of what his issues were, issues he said our culture won’t respond to because it would paint people of color as the reason for their own suffering. (You can guess the issues: black-on-black crime, dropout rates, teen pregnancy.) You know, just flat incorrect assumptions and lack of any work to find out that, yes, actually a lot of study has been done on those very subjects.

In response, I linked about 15 sources responding to each of the points he made, all of which popped on the first page of Google searches with a couple variations of key terms (I am an academic, after all). He read one, proceeded to double down on racial stereotyping, made some poor attempts at gas lighting me (“you’re an associate professor who gets paid for this kind of ‘knowledge?’), and shifted the topic three more times, quoting a really flat, racially troubling read of FBI crime stats. I responded with a few more articles for his new directions, only one of which he engaged and then said he was done reading.

That’s right, after two dissenting voices he was ready to proclaim his almost completely baseless claim that systematic racism no longer exists and black people are basically the source of their own suffering the Truth™.

That’s it. No more attempts at engagement. No more conversation. Just a full family block on Facebook from him and his wife. Not once did I get insulting. Not once did I tell him he was a bad person. Not once did I call out his unwillingness to see dissent as a personal moral failing. I really wanted to see what he did with the research he said wasn’t being done to address the issues he’d already decided he knew enough about.

It left me sad. This is so much of America. So many of our neighbors. So many people afraid to take seriously the deep racial rot that pervades the cultural fabric of this country. I understand the desire to wish things were different. To live colorblind lives alongside other colorblind people. To really and truly believe systemic racism collapsed under the weight of the Civil Rights Movement.

But I also understand the real harm caused by that fantasy. The real consequences of blinding ourselves to the legacy and present reality of racism in almost every facet of culture. I understand this because I’ve listened and read and studied. I understand this because of the life my daughter is living, not because of the one I am.

I spent the next few weeks thinking about the conversation, not so much replaying what was said as trying to tease out the guy’s absolute refusal to engage any of the sources I sent him. Even more, I wondered why he didn’t respond with sources of his own. I speculate that he didn’t have many to respond with, but that is an unsatisfactory, surface-level assumption on my part.

Mostly, I thought about what I know is true: it’s hard to get people to read in general, let alone to read about what they have no personal experience with. And that is a tough hill to climb when it comes to what it will take to break down the barriers racism has erected in our culture. It starts with relationships, but those are hard to make interpersonally in our self-segregated, digitally-mediated worlds.

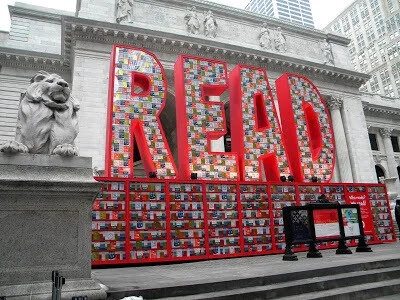

That’s why reading voices of color is so important. So necessary. These are the first relationships many people like Facebook guy need to have in order to change their perspectives.

This has always been my experience. Reading opens doors I didn’t see were there and introduces people I would never have met on the other side. And those introductions lead to changes in how I see the world and how deeply I feel for what I find there.

And that’s where my Black History Month books project came from. I thought through a list of texts by black authors I’ve read that continue to reshape how I see the world. Then I posted one a day for the entire month.

The list was never intended to be exhaustive, merely present a number of doors I hope people who haven’t yet done so will take the time to open.

Eulogies for Those Who Haven’t Left

Here's the opening of my essay, out today in The Other Journal. You can find the full essay here: https://theotherjournal.com/2018/02/27/eulogies-havent-left/

On Story and Captive Dolphins

Photo Courtesy: gratisography.com

Humans don’t have memories, just stories we’ve been told or told ourselves until words form prosthetic experience we carry inside in order to understand what happens outside of us. They form our experiences as our experiences form our next story.

Stories are our cipher, our codex, our record of what must be known and the tools we use to comprehend that record. Stories remember for us who we are and from where we come. But they are more than that. Stories are the air we breathe.

As a storyteller, I have a recurrent nightmare. Alzheimer’s disease. In broad terms, I can think of few potential terminal diagnoses more frightening than reaching the point at which my body continues on, in a biological sense, but my life ends, in the most practical sense of the words “life” and “ends.”

You see, without story there is no meaning, without meaning there is no hope, and without hope there is no life. This is not metaphorical. Hope extinguished is life’s cessation.

Note the discovery made of dolphins in captivity. At a certain point, some marine biologists contend, dolphins realize they are being held in a small tank rather than experiencing the freedom of the ocean. When they do, they just stop breathing. Respiration is a choice for dolphins, and, without hope, they choose to stop. Permanently.

I’d argue the same thing happens to humans when we cannot see a way for our story to continue. This is a massive claim, so let me reiterate: we live until our stories end.

And yet, we almost always take storytelling for granted. It’s a diversion or a pastime or, at most, something we do to communicate important information in a more accessible or entertaining form. But life-sustaining? That’s a bit much, right?

Here’s a challenge: turn to the nearest person and tell them about your childhood. The challenge? Do it without telling any stories. Really get them to understand where you came from and how it shaped you without painting a series of pictures that puts them there.

Better yet, try to clearly relay to that same person what it is to be human without resorting to narrative.

I am well aware that one may, via the means of scientific observation, make material claims as to the biological processes that comprise the collective meaning of the word “life” as applied to the human species. And yet that very word—life—is a story. Or, at present, more than seven billion stories intersecting and diverging every second of every day. The world is large, too large to know fully even with our best technological advances.

In the seminal 20th century novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez captures this dichotomy perfectly in the mystical gypsy elder Melquíades. Early in the story, he claims that, “Science has eliminated distance. In a short time, man will be able to see what is happening in any place in the world without leaving his house.” One might add that science may eventually make it possible to see what is going on inside anything in the world as well.

And yet, Melquíades then spends the rest of his life writing the story of the Buendía family, which the reader and even the characters of his story discover is really the process of writing the world of the novel into existence. Or, while science is murdering distance, that murder is merely a construct of the story being told about it.

In shorter form, meaning is the providence of story more than science. And in a fashion no data can replicate alone, stories convey the ways in which the parts of the world we will never experience personally are intimately similar to our own and the ways in which they could not be more different.

In essence, they allow us to live more than one life while simultaneously making the one life we are living fuller. Stories embed rather than explain, engage rather than instruct, influence rather than force change.

I understand freedom better because Frederick Douglass shared his slavery. Human bondage becomes experience through Alice Walker’s Celie. Golgotha’s footpath leads me to sacrifice. Flannery O’Connor’s Hazel Motes reminds me of my desperate need for someone to make a sacrifice on my behalf. Neil Gaiman’s stories hold potential futures I may live to see. Joan Didion’s essays and memoirs remind me of the present I must fight to remember I’m living. Gay Talese’s exhaustive profiles make characters of real people I’d like to meet but likely won’t. Cormac McCarthy’s invented characters are more real than most people I know.

What I gain through all of these stories is the hope that humanity’s story, “the powerful play” as Walt Whitman referred to it, continues in such a way that I may not only understand it better, but contribute my own stories to the collection. For what is more hopeful than the thought that my stories—stories that in my head seem so particular to me and me alone—may actually create hope for others?

So I tell stories, to anyone who will listen. I commit them to paper and screen with ink and code. I encourage them in others by begging them to look at their lives, at their words and images and very breathing, as a story they are in the midst of authoring.

It is in the telling of these stories that I have found (written?) the best response to the nightmare I described earlier. In it, I may have been robbed of my memory, but not of my stories. Rather, I imagine myself sitting in a chair, one of my children or readers or former students telling me a story, not merely for my benefit, but for their own as well.

In this way, my memories are safe in that they don’t really belong to me. Rather, they become the property and shared experience of anyone who comes in contact with them.

20

We are both creatures of perfectionism carrying so many things we wish we could take back in life so we could be perfect for each other. So many jagged edges the results of our pride and fear and silence and words we could have smoothed with better choices. Not for ourselves. For each other.

This is why we work. This is why those regrets are not anchors but balloons that float us even as we’d rather they didn’t exist. In fact, what I have learned in twenty years is that I prefer your mistakes to any perfections you could possibly create.

I don’t love who you wish you were. I love who you actually are. I love our scars because they mean we stayed long enough after falling to grow new skin. To be grafted back together when we were sure we’d cut each other so deeply our gashes wouldn’t heal.

Every stitch it’s taken to pull us back together has only bound us more tightly.

When we were 19, I told you I wanted you to marry me. Let’s just see if we make it through the summer, you said.

When we were 20, I told you I loved you more than I love myself. We won’t make it if that’s true, you said.

When we were 21, I told you I was afraid. Me too. Doesn’t that just mean this is important to us?, you asked.

When we were 22, I told you I was yours for life. I’ll never leave, you said.

When we were married, we made a number of promises. In the life we’ve lived since, these are the vows I carry most:

Christ in us, love in every moment, forgiveness without limit, truth especially when its hard, laughter in the face of darkness, and our hands in each others’ no matter the path we must walk.

I have been able to keep these vows because you have kept them too. Because you inspire me to get up when I fail, stay soft when I want to be hard, abandon my fear of being alone even when you are not with me. Every choice you’ve made is what allows me to be inspired this way.

I love you, not a version of what you could or might be someday. I love the flawed, real, perfectly genuine version I spend every day with. I don’t need you to change the past because the past is us. I don’t need you to become something different in the future because the future isn’t real.

All I need is you here in every moment, fingers between mine, laughter just behind the beautiful smile that is my sunrise, eyes looking to find me.

All I need is all you are. That’s all I’ve ever needed.

Re: Re:place

One of the coolest aspects of teaching what I do is the chance to work with young artists in new and interesting ways. The most recent version of this is a project I just completed and launched with eight grad students in my sorta bonkers digital literature course, Re:place.

A collaborative and genre-crossing project, Re:place revolves around the ways the places we find ourselves—Los Angeles in our case—draw us in and push us out, shaping how we see the rest of the world in the process. The final product was collaboratively conceived, planned, and executed over the course of the term and I am particularly proud of how it all came together.

Consider this, then, your formal invitation to come check out Re:place and consider your own in the process. After all, home visits us as much as we visit it.

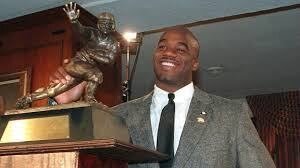

On the Death of Rashaan Salaam

The news came in a text first. Then a couple tweets filtered into my timeline, the first from ESPN’s Adam Schefter.

Rashaan’s dead. I guess as you get older, these moments happen more often. Mortality does not discriminate, and when someone like him dies, the rest of us, if we’re paying attention, take personal stock. At least for a moment.

When I say “someone like” Rashaan, I think that’s what’s kept him on my mind for the last 24 hours. I’m not going to claim we knew each other more than we did, which was to say we had a passing acquaintance as guys who ran track in the same league, though by virtue of talent, that league was not actually the same.

The most extensive conversation I can remember having with the guy was about the relative merits of the song “Check the Rhime” on A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory while we waited for a race to get called.

The thing is, Rashaan exists in a weird space between someone I knew and a hero, two boxes I would never place him in. Rather, he exists between, a shining satellite I came into orbit with simply because we ran that same races. That seems to be the case for many people trying to make sense of how he died.

He was neither my peer, nor my nemesis (that honor is taken by a guy named Ron Allen). No, I’d have had to have been faster for that to be the case. Because Rashaan was fast. Really fast. But that’s not the part of his story that gets told.

In the pre-internet world of the early 90s, Rashaan was an eight-man football phenomenon who drew national attention without the aid of YouTube, Vine, or the high school scouting apparatus that exists now. And it was warranted. Dude was crazy.

In a game against my high school, he ran a sweep to the left and one of our best players hit him perfectly below the knees, kicking his feet up over his head. Normal runners are happy not to have been injured by a hit like that. Rashaan put his free hand on the ground like he was doing a handstand, swung his legs back underneath himself, landed on his feet, and ran another 30 yards on the play.

What?

And that was not atypical. But I didn’t play football. So, when he went from tiny La Jolla Country Day to the University of Colorado Boulder to the Heisman Trophy to the Chicago Bears in the first round of the NFL draft, I watched as I had in high school: impressed to have seen him in person but not quite a fan, because he played for the other team.

Rashaan with the hardware. Image from ESPN.

Lost in the high school football legend and the perception of his unfulfilled pro potential is the fact that Rashaan could fly on the track. He wasn’t a pretty sprinter, like Carl Lewis or Usain Bolt. He ran like that yoked-up guy on the field, just faster without the pads to slow him down, as if he needed the unencumbering.

If he hadn’t been running in San Diego, in the early 90s, he’d have been touted as one of the fastest guys in his region. Unfortunately for him (and more so for me), that stretch from 1990 to 1998 was a golden age for high school sprinters in San Diego.

For a little context, Rashaan ran a 10.8-10.7 second 100 meter dash. That’s blazing. That kind of high school speed translates to a Division 1 scholarship for many runners (and could have for him had he wanted to focus on track). But that made him one of the second-tier runners when it came to the guys around him.

Guys like Darnay Scott (10.77), Johnny Robinson (10.77), Paul Turner (10.49), and Vince Williams (who would go 10.45 in 1996) all prevented him from being seen as a premier sprinter, not to mention the six other guys in the section running under 11 seconds I haven't named. And then there was Riley Washington, who still holds the CIF state meet record with his ridiculous 10.3 obliteration of the previous mark and the seven fastest guys in California not named Riley.

San Diego was home to several high schools that seemed like speed factories when I was coming up—Morse, Kearny, Lincoln Prep, Southwest, El Camino to name a few—so Rashaan’s freaky speed was, well, kinda ordinary in an extraordinary era. To get a sense of this, check out the 1991 state 200 meter final here, with Darnay and Riley in the race NOT winning.

But let me assure you, there’s looking at a runner’s time on paper, there’s watching them stop the watch on the screen, and then there’s the peculiar sense of having that speed imposed on you by someone who’s just gifted in ways you are not. That’s my clearest memory of Rashaan Salaam.

A brief bit of history, when Rashaan was a junior and I was a sophomore, I ended up running the open 400 against him at a meaningless dual meet . For the first 250 meters, it was very much like he was running and I was barely moving. But I’m fairly certain he was not training for the 400 at that point and he broke down physically, hitting what runners call the wall not once or twice, but three times, allowing me to reel him in and cross the line in a virtual tie.

Reminder: This was a meaningless meet. He would still go on to win the Heisman. I would never reach the CIF meet in the open 100 (his race). I only slightly celebrated in the moment, knowing that if he had cared at all or put in any time training, he would have smoked me. Then I forgot about it.

Apparently, he did not.

The next season we ended up in the same heat of my race, the 200 meter dash. As a junior, I was running just outside fast enough to make the open field at CIF sectionals, but just inside fast enough to end up in races with guys like Rashaan and Darnay. It was, as I’m sure you can imagine, not good for the ego.

This was the first time Rashaan and I had run against each other since the 400 the season before. What happened, I’ve never forgotten.

Rashaan started in lane two while I was in five, which meant I had a stagger of several meters when the gun went off. Also, I was stronger at the tactical thinking of running the curve than the brute speed of the straightaway. And, for once, I came out of the blocks quickly, which was unusual given my relatively tall 6’3” frame.

None of that mattered. The moment I was up and running, all I could hear was the sound of Rashaan’s feet striking the track once for every two strides of mine and his grunting with each footfall. He made up the stagger in the first 20 meters and THEN put the hammer down, rolling past me like I wasn’t even trying. It felt like he picked up a stride on me for every two I took, and no amount of digging deeper made any difference. With 50 meters to go, he was so far ahead he could have jogged the rest of the way.

I wish he had.

Instead, with 20 meters left, he turned and ran backwards, staring at me all the way through the finish line. I crossed about a half of a second later, but it might as well have been a year. I swear, it felt like he had time to pop a soda before I got there.

And that was it. No handshake or high-five or acknowledgement of any kind beyond the utter thrashing he gave me on the track. I only ever saw him again in the 4x100 relay (which we won). And then he was swallowed, by football first, and time after that. I hadn’t really thought about him much recently save on the rare occasions I ended up reliving my track days with old friends.

At least, that was true until yesterday, when they found his body in a park in the Boulder area, the one place he seemed to have been happy, or so I’ve read.

That’s the thing about guys like Rashaan. All we really know about them is left in that 21-second race, a quarter century ago.

New Short Story

Hey all. My short story, "Crossover," is out today in Angel City Review. Here's how it opens:

Nobody beat Ancient Jay to the court on Saturday. Billy knew this was true. He’d tried four times, once setting his alarm so he could get there before the sun came up over the houses on the hills that horseshoed Glen Park. It didn’t matter. Jay was there first.

Ancient Jay wasn’t really ancient. Probably late-thirties, forty tops. People called him ancient because he’d been playing pick up ball at the Glen longer than anyone else and because of his face. His sun-browned skin was creased like moist smoked jerky. Worse was the way Jay sweated. His pores were like little mouths drooling salty ooze that dribbled more than dripped. They never played shirts and skins and most guys called it the Jay Rule to his face. But Ancient Jay was a part of the park, constant like the swing set or sandbox or cement path winding through the two acres of grass and trees that smelled like pine and Pacific when the breeze blew through from the beach just across the Coast Highway. So the stories grew up around him. Billy knew the morning Jay wasn’t there would feel like someone took down the monkey bars and left up the slide....

You can find the rest of the story, and all of the stellar work in the winter edition of Angel City Review free at http://angelcityreview.com/.

A Roadmap or a Vacuum

I teach writing. Even when I'm teaching literature, I'm teaching how it was written as a way of seeing why it matters. Words matter to me, because they're never—never—just words.

A simple message of hearing and speaking critically is this: never view rhetoric as empty. How people argue their point is never merely an intellectual construct. It's a roadmap or it's a vacuum.

When you line up what people believe with why they believe it, you get one of those two possibilities in terms of how you can assess where their thinking will take them. Remember, words are never just words.

In some cases, you can see how an argument will play out in action. The sources and, often, the fallacies an arguer draws on to claim authority carry in them behaviors and message shapes the careful listener will find instructive in anticipating where this will go.

Hence: roadmap.

Example: Your friend tells you about a time a person of differing political views tore up a political sign they had posted in their yard. Your friend then points you to four separate Facebook posts describing similar behavior from "the same type" of people and, without pause, uses that in addition to their own experience to characterize all people they suspect as holding even similar political leanings as (fill in the negative characterization most employed by your friends/family/neighbors).

This, as we say in the business, is a fallacious two-fer. The first is the logical mistake of extending one's own personal experience too broadly in relation to the complexity and diversity of experiences found even in the limited world of yard sign destruction. Your friend's story becomes broad proof of their own feelings about "those people."

But everyone, even the most stubborn individualists, know their story isn't enough. Thus the second fallacy—a carefully cultivated mechanism for bias confirmation—becomes important. By linking to a few other friendly examples/perspectives, their own assertions are validated exponentially (in their heads, anyway). And that gives the confidence in their sweeping (and almost always wrong) generalizations-as-facts views.

And this becomes your map. This person will make their own opinions a truth stretched across an issue and act accordingly. It doesn't always tell you what they will do, merely how they will justify themselves after the fact (and yes, that is as scary to type as it is to consider in practice).

But a map is always better than the other option: the vacuum.

Taking the same sign vandalism, the vacuum rhetorician tells you the story and says, "That was wrong, the people who did it are bad, and I will never trust them again." And that's it; they've built a solid wall of certainty you can't see through to their reasoning.

These are not logical structures, they are the results of submerged processes that could hinge on all forms of fallacy or irrationality or even deep bias. But who knows, because this is the rhetorical equivalent of a kid responding to a math problem without showing his work. Right or wrong, you have no idea how that kid ended up where he did.

That's the vacuum. In terms of a math problem, it's confusing and counterproductive. In terms of the sign vandalism, it's problematic.

In terms of where we are in America today, it's terrifying.